|

|

|

Planning Home > General Plan > Mission Area Plan

Mission Area Plan

The Mission is a neighborhood of strong character and a sense of community developed over decades. This area is home to almost 60,000 people, with Latinos comprising over half the population. The Mission is bounded by Guerrero to the west, Potrero to the east, Division to the north and Cesar Chavez to the south. In addition to providing more than 23,000 jobs for the city of San Francisco, the Mission also provides a place for almost 60,000 residents to live, many in households substantially larger and poorer than those found elsewhere in the City. There are about 17,000 units of housing in the Mission mixed with commercial, industrial, retail and other uses. This mix of uses makes it possible for many residents to live and work in the same general area. Retail is a significant business type in the Mission. Mission and 24th Streets in particular offer a variety of shops and services including many small grocery stores, beauty shops and restaurants that serve the local neighborhood and reflect the Latino population. There are about 900 stores and restaurants in the Mission, employing nearly 5,000 people. Retail however, does not employ as many people as Production Distribution and Repair (PDR) activities. PDR businesses, concentrated in the northeast Mission, provide jobs for about 12,000 people, making PDR businesses the largest employers in the Mission. These businesses support San Francisco’s service and tourist industry and are comprised of everything from furniture makers, sound and video recording studios, wholesale distributors, auto repair shops, plumbing supply stores, lumber yards, and photography studios, to the large PG&E and Muni facilities. The Mission is known for its rich culture. It hosts annual public celebrations such as “Carnaval”, “Cinco de Mayo” and “Encuentro del Canto Popular” and houses a variety of community and cultural resources including Centro del Pueblo, the Mission Cultural Center, the Mission Economic Development Association, ODC, Cell Space, PODER, Saint Peters Housing, Dolores Street Community Services, the Bay Area Video Coalition, The Mission News and El Tecolote newspaper. Perhaps the most visible cultural resource however, are the many murals found throughout the area. These themed illustrations on the sides of buildings provide an historic and cultural context for residents and visitors alike. Overall, the Mission has a well-developed neighborhood infrastructure, easy access to shops and restaurants, an architecturally rich and varied housing stock, rich cultural resources, and excellent transit access. Traditionally a reservoir of affordable housing relatively accessible to recent immigrants and artists, housing affordability in the Mission has significantly declined in the past decade as condominium conversions have removed affordable rental housing and evicted low-income residents and families. Moreover, new housing has been largely unaffordable to existing residents, and constructed on land formerly occupied by PDR businesses. In addition to the Eastern Neighborhoods-wide goals outlined above, the following community-driven goals were developed specifically for the Mission, over the course of many public workshops:

This section presents the vision for the use of land in the Mission. It identifies activities that are important to protect or encourage and establishes their pattern in the neighborhood. This pattern is based on the need to increase opportunities for new housing development, particularly affordable housing, retain space for production, distribution and repair (PDR) activities, protect established residential areas, and build on the vibrant neighborhood commercial areas around Mission, Valencia and 24th Streets. Where and how these activities occur is critical to ensuring that future neighborhood change contributes positively to the city as well as the area’s vitality, fostering the Mission as a place to live and work. To ensure the Mission remains a center for immigrants, artists, and innovation, the established land use pattern should be reinforced. This means protecting established areas of residential, commercial and PDR, and ensuring that areas that have become mixed-use over time develop in such a way that they contribute positively to the neighborhood. A place for living and working also means a place where affordably priced housing is made available, a diverse array of jobs is protected, and where goods and services are oriented to serve the needs of the community. For the Mission to continue to function in this way, land must be designated for such uses and controlled in a more careful fashion. OBJECTIVE 1.1 Much of the Mission is mixed-use in character. Neighborhood commercial areas such as Mission, Valencia, and 24th Streets support a variety of activities, including shops and services, housing, small offices, and PDR businesses. Residential areas contain some small corner stores and other neighborhood-serving uses. The Northeast Mission is home to a unique mixture of activities which includes many important and successful PDR businesses, as well as offices, housing, retail and other uses. This mix of uses contributes to the vitality of the Mission and should be retained. The challenge in the Mission is to strengthen the neighborhood’s mixed-use character, while taking clear steps to protect and preserve PDR businesses, which provide jobs and services essential for the city. This Plan’s approach to land use controls in the Mission includes the following key elements:

The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 1.1.1 POLICY 1.1.2 POLICY 1.1.3 POLICY 1.1.4 POLICY 1.1.5 POLICY 1.1.6 POLICY 1.1.7 POLICY 1.1.8 POLICY 1.1.9 POLICY 1.1.10

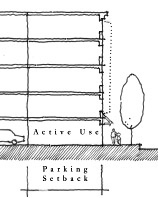

OBJECTIVE 1.2 It is important that new housing be developed in appropriate areas, that it be compatible with its surroundings, and that it satisfy community housing needs. Locating housing in neighborhood commercial areas with good transit, as well as in some portions of former industrial areas, allows new development to capitalize on existing infrastructure. By increasing development potential on some parcels, reducing parking requirements, and replacing existing unit density controls with “bedroom mix” controls that require a portion of new units to be larger and more family-friendly, more housing of the appropriate type can be encouraged. Strong building design controls, discussed further in the Built Form chapter of this Plan, should ensure that these new buildings are designed to be compatible with their surroundings. Building facades should be broken up, development above a certain height should be set back on small residential alleys to allow light and air, and active ground floors should be required. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 1.2.1 POLICY 1.2.2 POLICY 1.2.3 POLICY 1.2.4

OBJECTIVE 1.3 A notable characteristic of the Mission is that even in its industrial areas, there exists a unique and varied mix of offices, retail, housing and other uses, in addition to PDR businesses. The intent of the Plan is to create successful mixed areas where PDR uses can exist and compete well with other uses in the future. To ensure that the Mission’s unique mix remains in place, existing office and retail establishments in the Mission’s mixed-use and PDR districts should be allowed to stay legally, as long as they were legally established in the first place. Property owners whose office and retail tenants leave should be allowed to replace them with similar tenants. Existing legal nonconforming use rules already provide substantial protections to certain types of establishments that pre-date the proposed rezoning. For example, in areas where limitations will be imposed under new zoning on retail and office uses, existing office and retail uses that do not comply with this limitation would be able to remain, provided they were legally established in the first place. However, existing nonconforming rules do not apply to housing where it is prohibited outright. Because new zoning will create such districts, the nonconforming use provisions in the Planning Code should be modified in order to allow for the continuance of existing housing in areas where housing will no longer be permitted under the new zoning. The policies as well as implementing actions to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 1.3.1 POLICY 1.3.2 POLICY 1.3.3

OBJECTIVE 1.4 The “Knowledge Sector” consists of businesses that create economic value through the knowledge they generate and provide for their customers. These include businesses involved in financial services, professional services, information technology, publishing, digital media, multimedia, life sciences (including biotechnology), and environmental products and technologies. The Knowledge Sector contributes to the city’s economy through the high wages these industries generally pay, creating multiplier effects for local-serving businesses in San Francisco, and generating payroll taxes for the city. Although these industries generally require greater levels of training and education than PDR workers typically possess, they may in the future be able to provide a greater number of quality jobs for some San Franciscans without a four-year college degree, provided appropriate workforce development programs are put in place. From a land use perspective, the Knowledge Sector utilizes a variety of types of space. Depending on the particular needs of a company, this may include buildings for offices, research and development (R&D), and manufacturing. Mixed-use and industrial land in the Mission benefits from lower rents and less intensive development than other parts of the city. These characteristics may allow for the location of manufacturing and R&D components of the Knowledge Sector, as well as provide some “Class B” office space suitable for Knowledge Sector companies which cannot afford or would prefer not to be located downtown. These uses could be supported in the following manner:

The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 1.4.1 POLICY 1.4.2 POLICY 1.4.3

OBJECTIVE 1.5 Noise, or unwanted sound, is an inherent component of urban living. While environmental noise can pose a threat to mental and physical health, potential health impacts can be avoided or reduced through sound land use planning. The careful analysis and siting of new land uses can help to ensure land use compatibility, particularly in zones which allow a diverse range of land uses. Traffic is the most important source of environmental noise in San Francisco. Commercial land uses also generate noise from mechanical ventilation and cooling systems, and through freight movement. Sound control technologies are available to both insulate sensitive uses and contain unwanted sound from noisy uses. The use of good urban design can help to ensure that noise does not impede access and enjoyment of public space. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 1.5.1 POLICY 1.5.2

OBJECTIVE 1.6 Exposure to air pollutants can pose serious health problems, particularly for children, seniors and those with heart and lung diseases. Sound land use planning aims to reduce air pollution emissions by co-locating complementary land uses, which helps to decrease automobile traffic and encourage walkability and by avoiding land use-air quality conflicts that can result in exposure to air pollutants. While there are numerous social, environmental and economic benefits associated with integrating land use and transportation, there is also a potential risk of exposing residents to poor indoor air quality when infill residential developments are located in close proximity to air pollution sources, including traffic sources such as freeways or major streets. Epidemiologic studies have consistently demonstrated that children and adults living in proximity to busy roadways have poorer health outcomes, including higher rates of asthma disease and morbidity and impaired lung development. Given increasing demands for housing, particularly affordable housing, and the limited amount of available and suitable land for housing in San Francisco, it is important that the review process for proposed development projects incorporate analysis and mitigation of air quality conflicts, particularly with respect to sensitive land uses such as housing, schools, daycare and medical facilities. POLICY 1.6.1

OBJECTIVE 1.7 It is important for the health and diversity of the city’s economy and population that production, distribution and repair (PDR) activities find adequate and competitive space in San Francisco. PDR jobs constitute a significant portion of all jobs in the Mission. These jobs tend to pay above average wages, provide jobs for residents of all education levels, and offer good opportunities for advancement. However, they usually lease business space and are therefore subject to displacement. This is particularly important in the Mission as average household sizes tend to be larger and incomes lower than the rest of the city. Also, half of Mission residents are foreign born with two-thirds coming from Latin America and Mexico. Half of all Mission residents are of Latino heritage. About 45 percent of Mission residents speak Spanish at home. PDR businesses provide accessible jobs to many of these residents. PDR is also a valuable export industry. PDR businesses that design or manufacture products in San Francisco often do so because of advantages unique to being located in the city. These export industries present an opportunity to grow particular PDR sectors, strengthening and diversifying our local economy. PDR also supports the competitiveness of knowledge industries by providing critical business services that need to be close, timely and often times are highly specialized. Many PDR businesses form clusters, including arts activities, that are unique to San Francisco and provide services and employment for local residents. Establishing space for PDR activities that is protected from encroachment by other uses responds to existing policy set forth in the city’s General Plan, particularly the Commerce and Industry Element, which includes the following pertinent policies:

Generally, establishing areas for PDR businesses achieves the following:

The policies as well as implementing actions to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 1.7.1 POLICY 1.7.2 PDR districts proposed in this Plan were established to acknowledge and protect existing clusters of PDR activity and to provide an appropriate land supply to accommodate the city’s need for PDR businesses into the foreseeable future. Land use needs change over time, but case-by-case rezoning of individual parcels or groups of parcels within larger PDR districts would disrupt the integrity of the districts. Proposed rezoning should only be considered in the context of an evaluation and monitoring report of the Eastern Neighborhoods Plans, to be conducted by the Planning Department at five-year intervals. POLICY 1.7.3 Flexibly designed buildings with high floor to ceiling heights best accommodate the PDR businesses of today and tomorrow. Such spaces, equipped with roll-up doors or other large apertures, for example, facilitate the movement of goods and supplies. OBJECTIVE 1.8 Mission Street is well served by Muni and has two BART stations, at 16th and 24th streets. Directing new development along neighborhood commercial streets in the area, such as Mission and Valencia streets, increases their vitality as neighborhood commercial areas and takes advantage of existing transit infrastructure. A tremendous amount of this vitality is due to the unique character of the Mission’s neighborhood commercial areas, and that character should be encouraged and protected. Uses that are not community or neighborhood-serving should be managed in order to promote neighborhood serving and family-oriented businesses. To ensure compatibility with the existing scale of these areas, large lot development and lot mergers and business sizes should be carefully controlled. Because new zoning will allow for additional development capacity, more affordable housing should be required to address the needs of area residents and families. The existing Mission alcoholic beverage controls, restricting new bars and liquor stores, cover most of the Mission district. However in sections of Mission Street adult entertainment and tourist hotels are currently permitted with conditional use approval. To promote more community serving businesses in the Mission, these uses should be prohibited in neighborhood commercial areas. The policies to address the objective outlined above are as follows: POLICY 1.8.1 POLICY 1.8.2

Historically the Mission has been a valuable source of affordable housing for immigrants and families. There are about 60,000 people living in the Mission district, about half of whom are foreign born, mostly from Central America and Mexico. Median household incomes are lower and household sizes about 30% larger in the Mission than the city as a whole, and this is particularly true for Latino households which, according to the 2000 census, have a median household size of 3.8 and a median household income of $44,500. For the entire Mission, the median household size is 3 and the median income is $48,227, whereas the citywide median household size is 2.3 and the median income is $55,200. Although new housing continues to be constructed in the Mission, the majority of this housing is market-rate, owner-occupied and generally unaffordable to existing residents and families. The production of affordable housing is one of the main goals of the Mission Area Plan, in order to provide housing for neighborhood residents and others who are overburdened by their housing costs. “Affordable housing” refers simply to apartments or condominiums that are priced so as not to financially burden a household – housing costs that do not prevent individuals or families of any income level from affording other necessities of life, such as food, clothing, transportation and medical care. While the City has established affordability limits for individuals and families earning anywhere from about 30% to about 120% of the city’s median income, even families beyond that threshold have difficulty affording housing in San Francisco. What constitutes an affordable rent or mortgage is more specifically defined locally as a proportion of annual income for individuals and families. Households are categorized by income as very low-, low-, and moderate-income households based on their relation to the median income. (Median income is the level at which exactly half of the City’s households are above and half are below.) According to the Mayor’s Office of Housing, the median income for 2007 for a household with four members in San Francisco was $80,319. Yet the substantial majority of market-rate homes for sale in San Francisco are priced out of the reach of low- and moderate-income households - less than 10% of households in the City can afford a median-priced home. The City’s Inclusionary Affordable Housing Program is one existing method by which the City produces several Below-Market-rate (BMR) units to families and individuals’ earning below what is required to afford market prices. Under the amended 2006 Ordinance, market-rate developments of five units or more are required to include a mandatory fifteen percent of the project’s total units as BMRs, which are affordable to low and moderate-income buyers (for rentals, people earning below 60 percent of median; for ownership units, people earning between 80 and 120 percent of median). Alternatively, developments may select an equivalent option of off-site development or payment of in-lieu fee. However, this program only covers those earning up to 120 percent of median income, which in 2007 was $96,400 for a household of four. Yet even families earning more than this have difficulty affording housing in San Francisco. Almost 30 percent of its households fall in the bracket of moderate and middle incomes. Housing for working households remains one of the City’s greatest needs. The Mission Area Plan strives to meet six key objectives surrounding housing production and retention:

OBJECTIVE 2.1 The City of San Francisco has produced a significant number of market-rate units in the last five years, yet still has many units to produce at low, moderate and middle incomes if it is to meet the spectrum of need identified in the Housing Element of the General Plan. San Francisco’s Housing Element establishes the Plan Area, as well as the entirety of the Eastern Neighborhoods, as a target area in which to develop new housing to meet San Francisco’s identified housing targets in the category of low-, moderate- and middle-income units. A portion of the industrial lands of the Eastern Neighborhoods – areas formerly zoned for C-M, M-1, and M-2 , but not required to meet current PDR needs - offer an opportunity to zone areas to meet these identified categories of need. In order to facilitate the housing production percentage targets identified in the Housing Element, this plan sets forth new zoning districts on formerly industrial lands that enable the production of the type of housing San Francisco needs. In these new zoning districts, affordable housing would be permitted as of right. However, not all sites will be appropriate for the development of 100% affordable housing projects, or are available for development. In the area of the Mission generally known as the “Northeast Mission Industrial Zone” (NEMIZ) housing is permitted by conditional use according to the underlying industrial zoning. In recent years housing development has been restricted here by a series of interim policies from the Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors. Under the “mixed-income” housing requirements, in the formerly industrial zones, where market-rate housing was previously restricted, would be modified to allow developers a range of options to meet affordability needs. Those wishing to develop market-rate housing would be able to do so only under the following requirements:

Site developability in these areas will be increased by removal of density controls and in some cases through increased heights, to address the City’s most pressing housing needs. Single Resident Occupancy (SRO) units – defined by the Planning Code as units consisting of no more than one room at a maximum of 350 square feet - represent an important source of affordable housing in the Mission, representing about 9% of its housing stock. (There are an estimated 457 SRO Hotels in San Francisco with over 20,000 residential units, with most located in the Mission, Tenderloin, Chinatown, and South of Market). SRO units have generally been considered part of the city’s stock of affordable housing, and as such, City law prohibits conversion of SROs to tourist hotels. SROs serve as an affordable housing option for elderly, disabled, and single-person households, and in recognition of this, the Plan adopts several new policies to make sure they remain a source of continued affordability. Therefore, SROs are permitted as a category of housing available to moderate, middle-income and low income households.. In recognition of the fact that SROs serve small households, the Plan exempts SRO developments from meeting unit-mix requirements. In recognition of the fact that SROs truly are living spaces, and to prevent the kind of substandard living environments that can result from reduced rear yards and open spaces, this Plan requires that SROs adhere to the same rear yard and exposure requirements as other types of residential uses. Finally, the Plan calls for sale and rental prices of SROs to be monitored regularly to ensure that SROs truly remain a source of affordable housing, and that policies promoting them should continue. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 2.1.1 POLICY 2.1.2 POLICY 2.1.3 POLICY 2.1.4

OBJECTIVE 2.2 The existing housing stock is the City’s major source of relatively affordable housing. The Eastern Neighborhoods’ older and rent-controlled housing has been a long-standing resource for the City’s lower and middle income families. Priority should be given to the retention of existing units as a primary means to provide affordable housing. Demolition of sound existing housing should be limited, as residential demolitions and conversions can result in the loss of affordable housing. The General Plan discourages residential demolitions, except where they would result in replacement housing equal to or exceeding that which is to be demolished. The Planning Code and Commission already maintain policies that generally require conditional use authorization or discretionary review wherever demolition is proposed. In the Eastern Neighborhoods, policies should continue requirements for review of demolition of multi-unit buildings. A permit to demolish a residence cannot be issued until the replacement structure is approved. When approving such a demolition permit and the subsequent replacement structure, the Commission should review levels of affordability and tenure type (e.g. rental or for-sale) of the units being lost, and seek replacement projects whose units replaced meet a parallel need within the City. The goal of any change in existing housing stock should be to ensure that the net addition of new housing to the area offsets the loss of affordable housing by requiring the replacement of existing housing units at equivalent prices. The rehabilitation and maintenance of the housing stock is also a cost-effective and efficient means of insuring a safe, decent housing stock. A number of cities have addressed this issue through housing rehabilitation programs that restore and stabilize units already occupied by low-income households. While the City does have programs to finance housing rehabilitation costs for low-income homeowners, it could expand this program to reach large-scale, multi-unit buildings. Throughout the project area, the City could work to acquire and renovate existing low-cost housing, to ensure its long-term affordability. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 2.2.1 POLICY 2.2.2 POLICY 2.2.3 POLICY 2.2.4

OBJECTIVE 2.3 According to the Eastern Neighborhoods Socioeconomic Rezoning Impacts analysis, the Mission has a high concentration of family households relative to the rest of the city and even to other areas in the Eastern Neighborhoods. Close to 50 percent of all households in the Mission are family households, over 22 percent are households with children, and just fewer than 20 percent of the total population in the Mission are children under 18 years of age. Household size also tends to be greater in the Mission, with households with four or more people constituting a large percentage – 20 percent of households – while the share of housing units with one bedroom or no bedrooms is above 50 percent of all units in the area. Therefore, the Mission, which claims more than half of the Eastern Neighborhoods housing stock, shows the greatest mismatch between housing type and housing need. Overcrowding, defined by the U.S. Census bureau as more than one person per room, and severe overcrowding (more than 1.5 persons per room) is also greatest - over 6 percent overcrowded and 15 percent severe - in the Mission. The need for housing in the Mission covers the full range of tenure type (ownership versus rental) and unit mix (small versus large units). While there is a market for housing at a range of unit types, recent housing construction has focused on the production of smaller, ownership units. Policies in this plan are aimed to correcting this imbalance, in order to better serve families and renters. The Housing Element of the city’s General Plan recognizes that rental housing is often more affordable than for-sale housing, and existing city policies regulate the demolition and conversion of rental housing to other forms of occupancy. New development in the Mission area should ensure that rental opportunity is available for new residents as well. To try to achieve more family friendly housing, the Plan makes several recommendations. New development will be required to include a significant percentage of units with two or more bedrooms (SROs and senior housing will be exempted from this requirement). Family-friendly design should incorporate design elements such as housing with private entrances, on-site open space at grade and accessible from the unit, inclusion of other play spaces such as wide, safe sidewalks, on-site amenities such as children’s recreation rooms or day-care. The Planning Department can also encourage family units by drafting family-friendly guidelines to guide its construction, and by promoting projects which include multi-bedroom housing located in close proximity to schools, day-care centers, parks and neighborhood retail. Projects that met such guidelines could be provided faster processing time, including streamlined processing. One of the key priorities of the Mayor’s Office of Housing is expanding the stock of family, rental housing, with particular emphasis on very low and extremely low-income families. The Plan encourages the Mayor’s Office to maintain this priority in funding 100% affordable housing developments that provide safe, secure housing with multiple bedrooms and family-oriented amenities such as play areas and low-cost child care. In addition to the type of housing constructed, it is important to consider the services and amenities available to residents – transit, parks, child care, library services, and other community facilities. Many parts of the Eastern Neighborhoods are already underserved in many of these categories; and the lower income, family-oriented households of these neighborhoods, more than any other demographic, have a need for these services. The Plan aims to improve the neighborhoods, and to meet the needs that new residential units in the Eastern Neighborhoods will create, including increased demands on the area’s street network, limited open spaces, community facilities and services. New development will be required to contribute towards improvements that mitigate their impacts. The resulting community infrastructure, constructed through these funds and through other public funding, will benefit all residents in the area. The public benefits funds generated will support improvements to community infrastructure, including parks, transit, child care, libraries, and other community facilities needed by all new residents, but particularly needed by lower-income residents and families. Often, affordable housing exists in areas with poor neighborhood quality of life, poor access to transit and unreliable neighborhood services; yet the lower income households, more than any other demographic, have a need for these services. The public benefit policies intended to mitigate new development’s impacts will, in cooperation with other public funding, ensure that not only new housing, but also existing affordable housing, receives the community infrastructure a good neighborhood needs The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 2.3.1 POLICY 2.3.2 POLICY 2.3.3 POLICY 2.3.4 POLICY 2.3.5 POLICY 2.3.6

OBJECTIVE 2.4 There is a demonstrated need to reduce the overall cost of housing development and therefore reduce rental rates and purchase prices. Revising some requirements associated with housing development and expediting processing can help lower costs. The city’s current minimum parking requirement, for example, is a significant barrier to the production of housing, especially affordable housing. In much of the housing built under current parking requirements, the cost of parking is included in the cost of owning or renting a home, requiring households to pay for parking whether or not they need it. As part of an overall effort to increase housing affordability in the Plan Area, costs for parking should be separated from the cost of housing and, if provided, offered optionally. There are a number of design and construction techniques that can make housing “affordable by design” – efficiently designed, less costly to construct, and therefore less costly to rent or purchase. For example, forgoing structured parking can significantly reduce construction costs. Thus, as part of this Plan, parking requirements will be revised to allow, but not require parking. This provision will allow developers to build a reasonable amount of parking if desired and if feasible while meeting the Plan’s built form guidelines. Small infill projects, senior housing projects or other projects that may desire to provide fewer parking spaces would have the flexibility to do so. Also, conventionally framed low-rise construction is less costly than high-rise construction requiring steel and concrete. City actions including modifying zoning and building code requirements to enable less costly construction, as well as encouraging smaller room sizes and units that include fewer amenities or have low-cost finishes while not yielding on design and quality requirements can facilitate these techniques. Finally, the approval process for housing can be simplified, to reduce costs associated with long, protracted approval periods. Discretionary processes such as Conditional Use authorizations, and mandatory (i.e. non community initiated) Discretionary Review, should be limited as much as possible while still ensuring adequate community review. Provisions within CEQA should be used to enable exemptions or reduced review, including reduced traffic analysis requirement for urban infill residential projects. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 2.4.1 POLICY 2.4.2 POLICY 2.4.3 POLICY 2.4.4

OBJECTIVE 2.5 Well-planned neighborhoods - those with adequate and good quality housing; access to public transit, schools, and parks; safe routes for pedestrians and bicyclists; employment for residents; and unpolluted air, soil, and water - are healthy neighborhoods. Quality living environments in such neighborhoods have been demonstrated to have an impact on respiratory and cardiovascular health, reduce incidents of injuries, improve physical fitness, and improve social capital, by creating healthy social networks and support systems. Housing in the plan area should be designed to meet the physical, social and psychological needs of all and in particular, of families with children. Housing should also be designed to meet high standards for health and the environment. Green structures which use natural systems have better lighting, temperature control, improved ventilation and indoor air-quality which contribute to reduced asthma, colds, flu and absenteeism. Also, health-based building guidelines can help with health and safety issues such as injury & fall prevention; pest prevention; and general sanitation. To promote health at the neighborhood level, the San Francisco Department of Public Health has facilitated the multi-stakeholder Eastern Neighborhoods Community Health Impact Assessment (ENCHIA) to produce a vision for a healthy San Francisco as well as health objectives, measures, and indicators. The Department of Public Health (DPH) has worked with the Planning Department and other city agencies to assess the impacts, both positive and negative, of new development, and many aspects of this plan reflect those efforts. The policies are as follows: POLICY 2.5.1 POLICY 2.5.2 POLICY 2.5.3 POLICY 2.5.4

OBJECTIVE 2.6 The City already has programs in place to increase access and production of affordable housing, primarily though the Mayor’s Office of Housing. These existing programs, such as the inclusionary housing program, should be promoted and strengthened where economically feasible. Current city programs such as the second mortgage loans, first-time homebuyer, and down payment assistance programs should be promoted and expanded. To encourage private renovation of existing housing by low-income homeowners, programs that provide low-cost credit and subsidies to homeowners for the repair of code violations and target such subsidies to low-income households, especially families and seniors, should be initiated. And new models that reduce housing costs, such as limited equity models, location efficient mortgages and community land trusts, should be explored. Finally, programs, incentives and funding to increase housing production outside of the Mayor’s Office of Housing should be pursued, such as developer-supported housing initiatives, for-profit and non-profit developer partnerships as well as employer subsidies for workforce housing. In addition, there are a number of Citywide policies that can be modified to recognize population needs and growth. Units that are nonconforming or illegal, such as accessory units or housing in nonresidential structures, are often sources of affordable housing, and the City should continue to explore ways of legalizing such units. One prime example is live-work units, which as nonconforming units are limited in expansion. The City could enable live/work units to conforming status as a residential unit, provided they meet planning and building code requirements for residential space and pay retroactive residential development fees, e.g. school fees, as well as new impact fees that are proposed as part of this area plan. Finally, the City should work outside of the planning process to support affordable housing through citywide initiatives, such as housing redevelopment programs, and employer subsidies for workforce housing. The City should continue to work for increased funding towards its programs, utilizing outside sources such as state and regional grant funding as well as new localized sources. Property transfer taxes, tax increment, and City prioritization all offer potential dedicated funding streams that can provide needed revenue to the continued need for affordable housing. POLICY 2.6.1 POLICY 2.6.2 POLICY 2.6.3

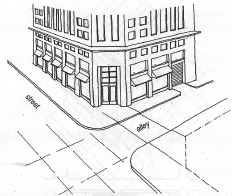

The many cultures, land uses, architectural styles, street grids and street types that exist within the Mission neighborhood define its character and set it apart from other areas of San Francisco. Indeed it is the coexistence and commingling, at times chaotic, of all these different elements that attracts most residents to the Mission. Urban design is central to defining how such a diverse physical and social environment is able to function, and will determine whether new additions contribute to, or detract from, the neighborhood’s essential character. The main purpose of this chapter is to strengthen the current character of the neighborhood, while allowing new development to positively contribute in an original way to the quality of life of residents, visitors and workers. The three main elements addressed here are height, architectural design and the role of new development in supporting a more ecologically sustainable urban environment. The policies and guidelines in this chapter will help to harmonize the old and the new. Where it is appropriate from an urban design and city building perspective, increase heights in those areas that are expected to see significant new development or that ought to have increased heights to support the city’s public transit infrastructure. The design of streets and sidewalks, an equally critical element in creating sustainable and enjoyable neighborhoods, is addressed in the Street and Open Space chapter of this Plan. OBJECTIVE 3.1 The Mission is one of the city’s most distinctive neighborhoods. To maintain this unique character in the face of new development we must ensure that buildings are of high-quality design and that they relate well to historic and surrounding structures. We must also ensure that new buildings enhance the quality of place and that ensure the neighborhood’s long-term livability and a compelling relationship to the rest of the city. Specific policies and design guidelines to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 3.1.1 POLICY 3.1.2 The tight integration of light industrial, mixed-use and residential buildings makes the NEMIZ a unique area in the city. All new development needs to strengthen the area’s traditional industrial character by choosing quality materials and finishes compatible with the existing fabric and by designing within a building envelope that is consistent with the surrounding context. New development should also recognize the building’s responsibility to provide architecturally interesting ground floors that contribute to, and not detract from, the pedestrian experience. POLICY 3.1.3 Generally, the height of buildings is set to relate to street widths throughout the Plan Area. An important urban design tool in specific applications is to frame streets with buildings or cornice lines that roughly reflect the street’s width. A core goal of the height districts is to create an urban form that will be intimate for the pedestrian, while improving opportunities for cost-effective housing and allowing for pedestrian-supportive ground floors. POLICY 3.1.4 Generally, the prevailing height of buildings is set to relate to street widths throughout the Plan Area. Height should also be used to emphasize key transit corridors and important activity centers. A primary intent of the height districts is to provide greater variety in scale and character while maximizing efficient building forms and enabling gracious ground floors. The scale of development and the relationship between street width and building height offer an important orientation cue for users by indicating a street’s relative importance in the hierarchy of streets, as well as its degree of formality. Taller buildings with more formal architecture should line streets that play an important role in the city’s urban pattern. POLICY 3.1.5 San Francisco’s natural topography provides important wayfinding cues for residents and visitors alike, and views towards the hills or the bay enable all users to orient themselves vis-à-vis natural landmarks. Further, the city’s striking location between the ocean and the bay, and on either side of the ridgeline running down the peninsula, remains one of its defining characteristics and should be celebrated by the city’s built form. Policy 3.1.6 Infill development should always strive to be the best design of the times, but should do so by acknowledging and respecting the positive attributes of the older buildings around it. Therefore, the new should provide positive additions to the best of the old, and not merely replicate the older architecture styles. POLICY 3.1.7 POLICY 3.1.8 POLICY 3.1.9 Important historic buildings cannot be replaced if destroyed. Their rich palette of materials and architectural styles imparts a unique identity to a neighborhood and provides valuable additions to the public realm. The Mission, as do the other inner-ring neighborhoods with an industrial past, demonstrates how adaptive reuse of historic buildings can provide a unique, identifiable, and highly enjoyed public place. Historic or otherwise notable buildings and districts should be celebrated, preserved in place, and not degraded in quality. See the Historic Preservation section of this area plan for specific preservation policies. POLICY 3.1.10 POLICY 3.1.11

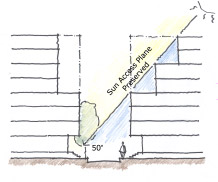

The alleyway network in the Mission offers residents and visitors the opportunity to walk through one of the most intimately-scaled environments in San Francisco. This feeling of intimacy is established by carefully balancing building height and setbacks so as to ensure a sense of enclosure, while not overwhelming the senses. Heights at the property line along both sides of alleys should be limited. In general, building height at the property line must not exceed 1.25 times the width of the alley. Above this height, a minimum 10-foot setback is required to maintain the appropriate and desired scale. POLICY 3.1.12 The narrowness of many of the Mission’s alleyways requires that development along them be carefully sculpted to proper proportions and to ensure that adequate light and air reach them and the frontages along them. In addition to the building height and setback requirements stated in Policy 3.1.10 above, the building height at the property line along the south side of east-west alleys, building height must be setback so as to ensure a 45-degree sun access plane, as extended from the property line on the opposite side of the street to the top corner of each story. Along both north-south and east-west alleyways, setbacks are not required for the first 60 linear feet of the alley from the adjoining major street, as measured from the property line along the major street, so as to allow a proper streetwall along that street. POLICY 3.1.13 The evolution of the city’s built fabric presents important opportunities to increase visual interest and create a special identity for the neighborhood. As one moves through the neighborhood, unexpectedly coming upon a view that terminates in a building designed to a higher standard generates an image unique to that place, while also helping to create a special connection to the built environment. OBJECTIVE 3.2 Achieving an engaging public realm for the Mission is essential. While visual interest is key to a pedestrian friendly environment, current development practice does not always contribute positively to the pedestrian experience, and many contemporary developments detract from it. Seeing through windows to the activities within – be they retail, commercial, or PDR – imparts a sense of conviviality that blank walls or garage doors are unable to provide. Visually permeable street frontages offer an effective and engaging nexus between the public and private domains, enlivening the street, offering a sense of security and encouraging people to walk. Where there are residential uses, seeing the activities of living is key, represented by stoops, porches and entryways, planted areas, and the presence of windows that provide “eyes on the street.” Specific policies and design guidelines to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 3.2.1

POLICY 3.2.2

POLICY 3.2.3

POLICY 3.2.4

POLICY 3.2.5

POLICY 3.2.6 In dense neighborhoods such as the Mission, streets can provide important and valued additions to the open space network, offering pleasurable and enjoyable connections for people between larger open spaces. San Francisco’s Better Streets Plan will provide guidance on how to improve the overall urban design quality, aesthetic character, and ecological function of the city’s streets while maintaining the safe and efficient use for all modes of transportation. POLICY 3.2.7

POLICY 3.2.8 POLICY 3.2.9

OBJECTIVE 3.3 Given the reality of global climate change, it is essential that cities, and development within those cities, limit their individual and collective ecological footprints. Using sustainable building materials, minimizing energy consumption, decreasing storm water runoff, filtering air pollution and providing natural habitat are ways in which cities and buildings can better integrate themselves with the natural systems of the landscape. These efforts have the immediate accessory benefits of improving the overall aesthetic character of neighborhoods by encouraging greening and usable public spaces and reducing exposure to environmental pollutants. Specific policies and design guidelines to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 3.3.1 The San Francisco Planning Department, in consultation with the Public Utilities Commission, is in the process of developing a green factor. The green factor will be a performance-based planning tool that requires all new development to meet a defined standard for on-site water infiltration, and offers developers substantial flexibility in meeting the standard. A similar green factor has been implemented in Seattle, WA, as well as in numerous European cities, and has proven to be a cost-effective tool, both to strengthen the environmental sustainability of each site, and to improve the aesthetic quality of the neighborhood. The Planning Department will provide a worksheet to calculate a proposed development’s green factor score. POLICY 3.3.2 POLICY 3.3.3 POLICY 3.3.5 The positive relationship between building sustainability, urban form, and the public realm has become increasingly understood as these buildings become more commonplace in cities around the world. Instead of turning inwards and creating a distinct and disconnected internal environment, sustainable buildings look outward at their surroundings as they allow in natural light and air. In so doing, they relate to the public domain through architectural creativity and visual interest, as open, visible windows provide a communicative interchange between those inside and outside the building. In an area where creative solutions to open space, public amenity, and visual interest are of special need, sustainable building strategies that enhance the public realm and enhance ecological sustainability are to be encouraged.

The Mission District’s compact built environment and its varied mix of uses make walking, bicycling and public transit attractive, high-demand transportation modes. Abundant transit options (local and regional), vibrant, pedestrian-scale commercial corridors (Mission Street, Valencia Street and 24th Street) and a popular network of bicycle lanes and routes make the Mission a great neighborhood to get around in without a car. The vision for an improved transportation system within the Mission District includes improvements for all modes, especially pedestrians and transit. Efforts to improve transit speed, reliability and the safety of pedestrians and bicyclists should not obstruct the loading and circulation needs of vehicles supporting the Mission’s PDR business activities. OBJECTIVE 4.1 The Mission’s several Muni lines and two BART stations make it an important local and regional transit hub. Commuters, residents and visitors from San Francisco and throughout the Bay Area pour in and out of the BART Stations at both 16th Street and 24th Street each morning and evening. Muni’s 14 and 49 buses which run along Mission Street carry almost 40,000 riders every day. The 48, 22, 33, and 9 bus lines also serve the Plan Area. Enhancements to existing transit service that improve speed and reliability should be made to reinforce the neighborhood’s existing transit orientation. Mission Street, 16th Street and Potrero Avenue stand out as desirable corridors to be considered for high-level transit improvements. These streets are called out in the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency’s (SFMTA) A Vision for Rapid Transit in San Francisco (2002) as corridors important to long-range transit planning. New bus rapid transit (BRT) service, transit signal priority, transit-only lanes, and/or lengthened distances between stops are some tools that should be explored further. The role of 16th Street as a key east-west transit corridor continues to grow as new development in the Eastern Neighborhoods and Mission Bay takes shape. Sixteenth Street is the only street that provides a continuous uninterrupted connection between the Mission, Showplace Square, Mission Bay and the eastern waterfront. It is also provides a critical link between local (Muni Third Street Light Rail) and regional transit (16th Street BART). The planned rerouting of the #22 bus down the full length of 16th Street to Mission Bay will help establish a major cross-town route in this developing area. Transit improvements for the 16th Street corridor are needed to accommodate increased transit service and to ensure transit vehicles are not crippled by congestion. Collaborative planning between city agencies, BART, businesses and large land holders like UCSF is necessary to design a transit corridor that prioritizes transit while serving the diverse land uses along the corridor. Transit improvements on 16th Street will also benefit the existing PDR businesses and employees found in the area that are expected to stay and grow. Beginning in 2008, the SFMTA, Planning Department and the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (SFCTA) will commence a comprehensive Eastern Neighborhoods Transportation Implementation Planning Study (EN TRIPS) to further explore the feasibility of the options described above, determine which projects are needed, how they should be designed and how they can be funded. A key input to this will be SFMTA’s “Transit Effectiveness Project” (TEP), the first comprehensive study of the Muni system since the late 1970s. The TEP aims to promote overall performance and long-term financial stability through faster, more reliable transportation choices and cost-effective operating practices The TEP recommendations focus on improving transit service, speed and reliability and should be implemented as soon as possible within the Mission area. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 4.1.1 This policy refers to the Eastern Neighborhoods Transportation Implementation Planning Study described above: POLICY 4.1.2 POLICY 4.1.3 POLICY 4.1.4 Curb cuts should be reduced on key neighborhood commercial, pedestrian, and transit streets, where it is important to maintain continuous active ground floor activity, reduce transit delay and variability, and protect pedestrian movement and retail viability such as Mission, Valencia, 16th and 24th Streets. This is critical measure to reduce congestion and conflicts with pedestrian and transit movement along Transit Preferential Streets, particularly where transit vehicles do not run in protected dedicated rights-of-way and are vulnerable to disruption and delay. POLICY 4.1.5 POLICY 4.1.6 POLICY 4.1.7 As a core PDR area served by a major transit route (Muni’s #22 bus), 16th Street and neighboring parcels illustrate the conflicts between the competing policy goals of improving transit and preserving PDR businesses. PDR land uses in the Mission and Showplace Square should be preserved to support the critical business activity they provide. However, PDR-related truck traffic, loading and circulation needs can slow transit vehicles. Further planning and design work is needed to make 16th Street a better transit street by mitigating the impacts of surrounding land uses. For example, off-street truck loading requirements and transit-signal priority can improve 16th Street for transit while continuing to support the neighboring PDR land uses. POLICY 4.1.8 Additional transit vehicles will be needed to serve new development in the Eastern Neighborhoods. The capacity of existing storage and maintenance facilities should be expanded and new facilities constructed to support growth in the Eastern Neighborhoods. OBJECTIVE 4.2 A transit rider’s experience is largely impacted by the quality of environment in and around the stops and stations where they start or end their transit trips. Transit stops can be made more attractive and comfortable for riders through installation of bus bulbs, shelters, additional seating, lighting, and landscaping. Pedestrian safety should also be prioritized near transit through the installation and maintenance of signs, crosswalks, pedestrian signals and other appropriate measures. Quality passenger information such as maps directing riders to major destinations, and accurate real-time transit information should be provided. Key transit stops with high passenger volumes or where transfers occur should be prioritized for enhanced amenities. In the Mission, these key stops may include 16th Street and Mission, 24th Street and Mission, 16th street and Potrero Avenue among others. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 4.2.1 POLICY 4.2.2

OBJECTIVE 4.3 The Mission’s dense concentration of housing along with its vibrant mix of restaurants, neighborhood services, shopping and nightlife all generate a high demand for parking. Determining how existing and new parking is managed in the Mission is essential to achieving a range of community goals including reduced congestion and private vehicle trips, improved transit, successful commercial areas, housing production and affordability, and attractive urban design. Elimination of minimum off-street parking requirements in new residential and commercial developments, while continuing to permit reasonable amounts of parking if desired, allows developers more flexibility in how they choose to use scarce developable space. In developments where space permits or where expected residents would particularly desire to own cars, parking can be provided, while in transit intensive areas, or where expected residents would not need cars (senior developments for example) parking would not be required. Space previously dedicated to parking in residential developments can be made available for additional housing units. With no parking minimums and therefore no need for individual drive-in parking spaces, new residential and commercial developments can explore more efficient methods of providing parking such as mechanical parking lifts, tandem or valet parking. “Unbundling” parking from housing costs can reduce the cost of housing and make it more affordable to people without automobiles. The cost of parking is often aggregated in rents and purchase prices. This forces people to pay for parking without choice and without consideration of need or the many alternatives to driving available in the Mission. This could be avoided by requiring that parking be separated from residential or commercial rents, allowing people to make conscious decisions about parking and auto ownership. Proper management of public parking, both on-street and in garages is critical. Currently, on-street parking is difficult to find in many parts of the city. Loose regulation and relatively inexpensive rates increase demand and decrease turnover of parking spaces. This shifts demand away from public transit and other modes, increases congestion and encourages long term on-street parking by employees and commuters. To support the needs of businesses and create successful commercial areas, on-street parking spaces should be managed to favor short-term shoppers, visitors, and loading. In residential areas, curbside parking should be managed to favor residents, while allocating any additional spaces for short-term visitors to the area. Recent research has proposed a number of ways to use market-based pricing and other innovative management techniques to improve availability of on-street parking while also increasing the revenue stream to the city. These methods are currently under study and should be applied in this area. In accordance with Section 8A.113 of Proposition E (2000), new public parking facilities can only be constructed if the revenue earned from a new parking garage will be sufficient to cover construction and operating costs without the need for a subsidy. New development built with reduced parking could accommodate parking needs of drivers through innovative shared parking arrangements like a “community parking garage.” Located outside of neighborhood commercial and small scale residential areas, such a facility would consolidate parking amongst a range of users (commercial and residential) while contributing to the neighborhood with an active ground floor featuring opportunities for neighborhood services and retail. The policies as well as implementing actions to address the objective outlined above are as follows: POLICY 4.3.1 POLICY 4.3.2 POLICY 4.3.3 POLICY 4.3.4 POLICY 4.3.5 POLICY 4.3.6 The San Francisco County Transportation Authority is conducting the On-Street Parking Management and Pricing Study to evaluate a variety of improved management techniques for on-street parking and recommend which should be put into effect in San Francisco. OBJECTIVE 4.4 A significant share of deliveries to PDR and other businesses in the Mission are performed within the street space. Where curbside freight loading space is not available, delivery vehicles double-park, blocking major thoroughfares like Mission Street, slowing transit and creating potential hazards for pedestrians, bicyclists and automobiles. The City should evaluate the existing on-street curb-designation for delivery vehicles and improve daytime enforcement to increase turnover. Where necessary, curbside freight loading spaces should be increased. During evenings and weekends, curbside freight loading spaces should be made available for visitor and customer parking. In new non-residential developments, adequate loading spaces internal to the development should be required to minimize conflicts with other street users like pedestrians, bicyclists and transit vehicles. POLICY 4.4.1 POLICY 4.4.2 POLICY 4.4.3

OBJECTIVE 4.5 Not only are streets essential for movement, but they are a major component of the city’s public realm and open space network. The Mission’s streets and sidewalks move people and goods as well as provide places to sit, talk and stroll. Past sale of streets or rights-of-way to accommodate private development has impeded connectivity and mobility in some parts of San Francisco. Future closure and sale of city streets to private development should be discouraged unless it is determined excess roadway or reconfiguration of specific intersection geometries will achieve significant public benefits such as increased traffic safety, pedestrian safety, more reliable transit service or public open space. New developments on large lots must consider alleys to break up the scale of the building and allow greater street connectivity. POLICY 4.5.1 POLICY 4.5.2

OBJECTIVE 4.6 The Mission’s primary commercial corridors - Mission, Valencia and 24th Streets – are crowded with pedestrians. Storefront retail, street level art and murals, good transit, well-marked crosswalks, and pedestrian signals all support a strong walking environment. However, conflicts with vehicles continue to present pedestrian safety concerns in the neighborhood. Opportunities exist to further improve pedestrian safety and accessibility in the Mission. Several studies related to pedestrian improvements in the Mission have been completed or are in the planning stages. Recommendations from the Southeast Mission Pedestrian Safety Plan produced by SFMTA and the Department of Public Health should be implemented. In addition, the Planning Department is working with the SFMTA to develop the Mission Public Realm Plan and Better Streets Plan to ensure the Mission’s streets are designed to promote pedestrian comfort and safety. The planned widening of Valencia Street’s sidewalks should also be seen through to completion. In 2008, the Planning Department will be leading a planning process for the redesign of Cesar Chavez Street to make the street function better for pedestrians, bicyclists and transit. Where possible, the city should implement high-visibility crosswalks, pedestrian signal heads with countdown timers, corner bulbouts, median refuge islands, or other pedestrian improvements. In specific areas with known higher rates of pedestrian-collisions, developers should be encouraged to carry out context specific planning and design on building projects to improve pedestrian safety. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 4.6.1 POLICY 4.6.2 POLICY 4.6.3

OBJECTIVE 4.7 The Mission’s existing bicycle infrastructure and relatively flat terrain create an attractive bicycling environment. The Valencia and Harrison Street bicycle lanes are busy with bicyclists during commute times and throughout the day. These lanes provide good north-south bicycle connections, but the Mission lacks strong east-west bicycle facilities. Improvements are planned to strengthen east-west connections. The SFMTA currently has improvements planned for Cesar Chavez and 17th Streets. Bicycle lanes and shared lane markings (“sharrows”) on select segments of these streets will be installed once the San Francisco Bicycle Plan achieves environmental clearance. In addition, increased bicycle parking throughout the Mission especially in commercial areas and near BART is needed to accommodate the ever increasing number of bicyclists. Recent citywide zoning code amendments require bicycle parking for all new developments. The proposed Mission Creek Bikeway presents the opportunity for a future landscaped bicycle path from the Mission District to Mission Bay. Bikeway plans should be further examined, especially issues surrounding cost and implementation. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 4.7.1 POLICY 4.7.2 POLICY 4.7.3

OBJECTIVE 4.8 In addition to investments in our transportation infrastructure, there are a variety of programmatic ways in which the City can encourage people to use alternative modes of travel. Car sharing and transportation demand management programs (TDM) are important tools to reduce congestion and limit parking demand. Carsharing offers an affordable alternative to car ownership by allowing individuals the use of a car without the cost of ownership (gas, insurance, maintenance). Carsharing companies provide privately owned and maintained vehicles for short-term use by their members. Carshare members pay a flat hourly rate or monthly fee to use cars only when they need them (i.e. to run errands or make short trips). The Mission already has a high concentration of car share vehicles, especially near the Mission and Valencia corridors. Recent zoning code changes require carshare spaces in new residential developments. Car sharing should continue to be encouraged in the Mission as part of new residential and commercial developments in support of parking policies and increased mobility of residents without automobiles. “Transportation demand management” (TDM) programs that encourage residents and employees to walk, bike, take public transit or rideshare should be implemented in the Mission and throughout the Eastern Neighborhoods. Transportation Demand Management (TDM) combines marketing and incentive programs to reduce dependence on automobiles and encourage use of a range of transportation options. Cash-out policies (where employers provide cash instead of a free parking space), Commuter Checks and emergency ride home programs are some of the methods institutions and employers can utilize. City College of San Francisco’s new Valencia Street campus, among other large institutions and employers should be encouraged to develop programs that provide information and incentives to students and staff related to the many transportation alternatives nearby. Major residential developments (50+ units) should be required to provide transit passes to all residents as part of rent or homeowner association fees. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 4.8.1 POLICY 4.8.2 POLICY 4.8.3

OBJECTIVE 4.9 Automobiles in the Mission navigate streets crowded with pedestrians, bicyclists and transit vehicles. Vehicle traffic should be accommodated without jeopardizing the safety of other street users. Traffic calming projects should be implemented to reduce speeding and improve safety, without introducing delay or reliability problems for transit. Guerrero Street and South Van Ness Avenue provide opportunities for traffic calming to balance neighborhood and pedestrian needs with auto traffic. New technologies such as those being developed by the Department of Parking and Traffic’s “SFGO” program should be pursued to reduce congestion, respond to current traffic conditions and move autos safely and efficiently. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: POLICY 4.9.1 POLICY 4.9.2

OBJECTIVE 4.10 New development in the Mission and throughout the Eastern Neighborhoods will exert significant strain on the area’s existing transportation infrastructure. The City must develop new funding sources and a funding plan to ensure needed improvements are made. Transportation improvements are costly. While federal, state, regional and local grant sources are available to partially defray the cost of transportation capital projects, they are not sufficient to meet transportation needs identified by the community. Streets and transportation improvements (pedestrian, bicycle, and transit) will require a significant portion of the funding generated through the Eastern Neighborhoods Public Benefits Program. Because funds from this program will also be needed to support a number of other community improvements beside transportation, it will be important to identify additional sources of funding. POLICY 4.10.1

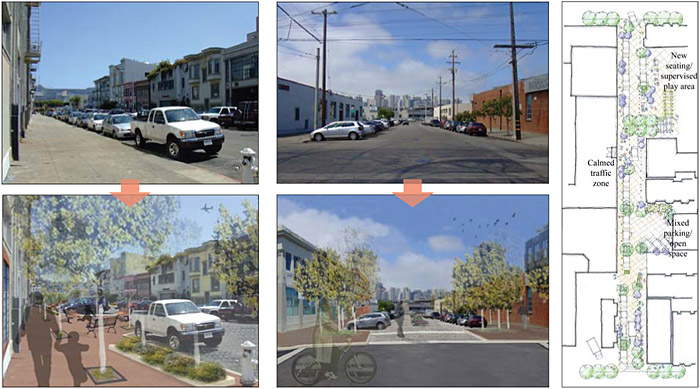

The Mission has a deficiency of open spaces serving the neighborhood. Some portions of the Mission historically have been predominantly industrial, which has meant that many areas are not within walking distance to an existing park and many areas lack adequate places to recreate and relax. Moreover, the Mission has a concentration of family households with children -- almost 50% -- which is significantly higher than most neighborhoods in the city. With the addition of new residents, this deficiency will only be exacerbated. Thus, one of the primary objectives of this Plan is to provide more open space to serve both existing and new residents, workers and visitors. Analysis reveals that a total of about 4.3 acres of new space should be provided in this area to accommodate expected growth. This Plan proposes to provide this new open space by creating at least one substantial new park site in the Mission. In addition, the Plan proposes to encourage some of the private open space that will be required as part of development to be provided as public open space and to utilize our existing rights-of-way to provide pocket parks. OBJECTIVE 5.1 In a built-out neighborhood such as this, finding sites for sizeable new parks is difficult. However, it is critical that at least one new substantial open space be provided as part of this Plan. The Planning Department will continue working with the Recreation and Parks Department to identify a site in the Mission for a public park and will continue to work to acquire additional open spaces. In order to provide this new open space, significant funding will need to be identified to acquire, develop, and maintain the space. One source of funds would be impact fees or direct contributions from new development. New residential development directly impacts the existing park sites with its influx of new residents, therefore new residential development will be required to either pay directly into a fund to acquire new open space. Commercial development also directly impacts existing park sites, with workers, shoppers and others needing places to eat lunch and take a break outside. Existing requirements in the Mission for commercial development establish a minimum amount of open space to be provided on-site, or project sponsors may elect to pay an in-lieu fee. Because these fees are low, project sponsors often elect to pay the fee. This Plan proposes to maintain the current requirements for commercial development to provide adequate, usable open space, but increase the in-lieu fee if project sponsors choose not to provide this space. This in-lieu fee will be used to provide publicly accessible open space. The policies to address the objective above are as follows: Policy 5.1.1 Policy 5.1.2