|

|

|

Planning Home > General Plan > Urban Design Element

Urban Design Element

INTRODUCTION Nature and Purpose The Urban Design Element concerns the physical character and order of the city, and the relationship between people and their environment. San Francisco's environment is magnificent, and the city is a great city, but the unique relationships of natural setting and man's past creations are extremely fragile. There are constant pressures for change, some for growth, some for decay. The Urban Design Element is concerned both with development and with preservation. It is a concerted effort to recognize the positive attributes of the city, to enhance and conserve those attributes, and to improve the living environment where it is less than satisfactory. The Plan is a definition of quality, a definition based upon human needs. This is a general plan, responding to issues relating to City Pattern, Conservation, Major New Development, and Neighborhood Environment. In the case of each of these four types of issues, the Element contains:

Human Needs

To describe the pattern is not to describe a rigid order, for rigidity will not produce a city meant for human needs. Rather than rigidity, the sense is one of balance and compatibility, with diverse and even random features fitting together to form the whole. The pattern is made up of: WATER, the Bay and Ocean, which are boundaries for the city and a part of its climate and way of life. The water is open space, a focus of major views and a place of human activity. HILLS AND RIDGES, which allow the city to be seen, define districts, and more than any other feature produce the variety that is characteristic of San Francisco. The central mass of Twin Peaks separates the city into quadrants, for example, while Telegraph Hill, Sunset Heights and Potrero Hill are neighborhoods. In the topographic form of the city, the valleys and plains are as important as the hills, for they define their own districts and give the hills their visual meaning. OPEN SPACES AND LANDSCAPED AREAS, whose dark green patterns enrich the color of the city and define and identify hills, districts and places for recreation. These areas may be large, as at the Presidio, Lake Merced and Golden Gate Park, smaller but still prominent as at Bayview Hill and Alta Plaza, or mixed with buildings as on the slopes of Russian Hill and Buena Vista. STREETS AND ROADWAYS, which unify the pattern, emphasize the hills and valleys, provide vistas and open space and determine the character of development. Streets and roadways are of many types, each with its own functions and characteristics, and together they make up a system that accommodates man's movements and joins the districts of the city. BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES and clusters of them, which reflect the character of districts and centers for activity, provide reference points for human orientation, and may add to (but can detract from) topography and views. Some buildings and structures, such as the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges, Coit Tower, the Palace of Fine Arts and City College, stand out as single features of community importance, while elsewhere the dominant pattern of man's development is a light-toned texture of separate shapes blended and articulated over the landscape.

The uses and benefits of the city pattern are many and profound. This pattern is, first of all, bound up in the image and character of the city. To weaken or destroy the pattern would make San Francisco a vastly different place. Second, the city pattern has important psychological effects upon residents of the city. It provides organization and measured relationships that give a sense of place and purpose and reduce the degree of stress in urban life. Outlooks upon a pleasant and varied pattern provide for an extension of individual consciousness and personality, and give a comforting sense of living with the environment. The pattern also helps people to identify districts and neighborhoods, particularly those in which they themselves live. Recognition of such areas by their prominent features, their edges and their centers for activity breaks up a large and intense city into units that are visually and psychologically manageable. Furthermore, awareness of districts and neighborhoods increases the pride in one's area and in one's own life. People also have a need to understand their city, its logic and its means of cohesion. They need to know where to find activities, and how to reach their destinations in shopping areas, downtown, at institutions and at places of entertainment and recreation. The city pattern helps them find their way, without inconvenience or lost time, letting them see the routes to be taken. Travel congestion is reduced if the best routes are easily found, and safety is increased.

The human needs outlined above for the city pattern are further addressed by the fundamental principles that follow, and by the policies that conclude this section of The Urban Design Element. In certain ways they are addressed, as well, in the other three sections of the Element: by policies dealing with conservation of resources that are part of the city pattern; policies for moderation of major new development to enhance rather than detract from the city pattern; and policies to make the pattern more perceptible in the neighborhood environment. Such an interchange of needs and policies occurs throughout the sections of the Element, for the Element is a unified document and its sections are closely related. OBJECTIVE OBJECTIVE 1

San Francisco has an image and character in its city pattern which depend especially upon views, topography, streets, building form and major landscaping. This pattern gives an organization and sense of purpose to the city, denotes the extent and special nature of districts, and identifies and makes prominent the centers of human activity. The pattern also assists in orientation for travel on foot, by automobile and by public transportation. The city pattern should be recognized, protected and enhanced.

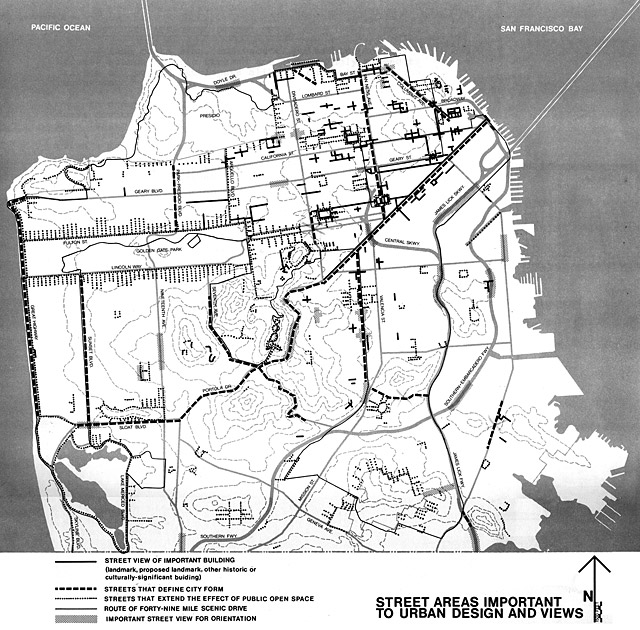

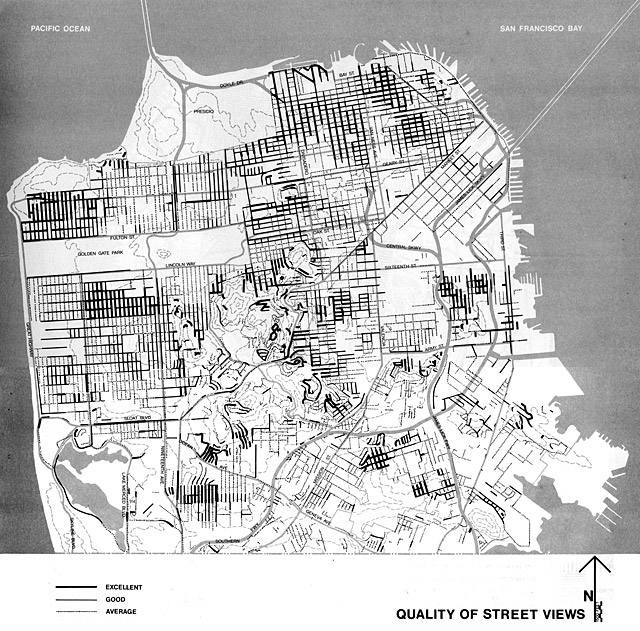

Image and Character POLICY 1.1 Views contribute immeasurably to the quality of the city and to the lives of its residents. Protection should be given to major views whenever it is feasible, with special attention to the characteristic views of open space and water that reflect the natural setting of the city and give a colorful and refreshing contrast to man's development. Overlooks and other viewpoints for appreciation of the city and its environs should be protected and supplemented, by limitation of buildings and other obstructions where necessary and by establishment of new viewpoints at key locations. Visibility of open spaces, especially those on hilltops, should be maintained and improved, in order to enhance the overall form of the city, contribute to the distinctiveness of districts and permit easy identification of recreational resources. The landscaping at such locations also provides a pleasant focus for views along streets. POLICY 1.2 Streets are a stable and unifying component of the city pattern. Changes in the street system that would significantly alter this pattern should be made only after due consideration for their effects upon the environment. Such changes should not counteract the established rhythm of the streets with respect to topography, or break the grid system without compensating advantages. The width of streets should be considered in determining the type and size of building development, so as to provide enclosing street facades and complement the nature of the street. Streets and development bordering open spaces are especially important with respect to the strength and order in their design. Where setbacks establish facade lines that form an important component of a street's visual character, new and remodeled buildings should maintain the existing facade lines. Streets cutting across the normal grid pattern produce unusual and often beneficial design relationships that should not be weakened or interrupted in building development. Special consideration should be given to the quality of buildings and other features closing major vistas at the ends of these and other streets. POLICY 1.3 Buildings, which collectively contribute to the characteristic pattern of the city, are the greatest variable because they are most easily altered by man. Therefore, the relationships of building forms to one another and to other elements of the city pattern should be moderated so that the effects will be complementary and harmonious. The general pattern of buildings should emphasize the topographic form of the city and the importance of centers of activity. It should also help to define street areas and other public open spaces. Individual buildings and other structures should stand out prominently in the city pattern only in exceptional circumstances, where they signify the presence of important community facilities and occupy visual focal points that benefit from buildings and structures of such design. The form of buildings is covered in greater detail in this Plan under the section on Major New Development. POLICY 1.4 Open spaces provide a unifying and often continuous framework across the city. These open spaces are most prominent when they occur on hills and ridges and when they contain large trees and other large-scale masses of landscaping. Future landscaping efforts, both public and private, should be directed toward preservation of existing trees and other planting that contribute to this framework, and toward addition of large-scale landscaping that will add to and fill out the framework. Where open spaces of any kind can be made more prominent by addition of new or large-scale landscaping, such additions should be made in order to enhance the city pattern and make the open spaces more visible in nearby neighborhoods. New building development should respect existing landscaping and avoid displacing or obscuring it. In the event that such landscaping must be displaced or obscured, a strong effort should be made to replace it with new landscaping of equal or greater prominence. Organization and Sense of Purpose POLICY 1.5

The design of improvements for street areas, and to some extent for private properties as well, should capitalize on opportunities to emphasize the distinctive nature of districts and neighborhoods. Street landscaping, in particular, can be selected and designed according to a special theme for each area, providing a sense of place in addition to its other amenities. Planting for public open spaces and on private properties can be carried out in the same way, taking account of established themes and the differences in climate among districts. Distinctiveness can also be imparted by preservation and highlighting of architectural features common to the area, and the use of special materials and colors in buildings. POLICY 1.6 Shopping streets and other centers for activity and congregation of people should stand out in an attractive manner in their districts. Some such centers, in appropriate cases, will have buildings larger than those in the surrounding area, while others will be set off only by their distinctive design treatment. Street landscaping of a type and size appropriate to the area should be used, as well as lighting that identifies the area through special fixtures and quality of light. Sidewalk treatment should be coordinated, with distinctive paving, benches and other elements suitable to the needs and desires of merchants, shoppers and other people using the area. Building facades and the total composition of the activity center should be designed to make clear the geographical extent of the center and its relationship to the district. POLICY 1.7 Visually prominent features such as hills, roadways and large groves of trees often identify the edges of districts and neighborhoods. Although these features should not be regarded as barriers to movement from one area to another, they do have the advantage of creating an awareness of districts and neighborhoods within the total city pattern. The positive effects of natural district boundaries should be emphasized in decisions affecting visually prominent features such as new roadways and large-scale landscaping. At the same time these same types of features can be useful links between districts, and between parks and other public and semi-public facilities. Connections between districts and facilities should be improved, with special attention to the possibilities for landscaped pathways that will provide an alternative to the street system in movement about the city. Orientation for Travel POLICY 1.8 In travel about the city, the ability to see one's destination and other points of orientation is an important product of the city pattern. Such an ability should be fostered in public and private development.

The design of streets, the determination of street use and the control of land uses and building types along streets should all be carried out with the visibility of such orienting features taken into account. Views from streets and other public areas should be preserved, created and improved where they include the water, open spaces, large buildings and other major features of the city pattern. Entranceways to the city and to districts are of special concern in this respect, as are lateral and downhill views that show a panorama or corridor with prominent features. POLICY 1.9 Many types of improvements can be made in street areas and in their surroundings to provide greater clarity and increase the ease of travel. Once such improvements have been made, adequate maintenance of them is of equal importance. Among the least difficult actions would be development of a better system of identifying and directional signs, through improvement of verbal messages, symbols, graphic design and sign placement. Although trafficway signs should be improved, the purpose and direction of traffic channels should also be made as clear as possible through design of the channels themselves. The roadway should be consistent in width and materials, with channels separated by islands and dividers where possible and changes of direction made distinct. At intersections, the differences in importance and function of the intersecting streets should be made visually clear by differences in roadway width, landscaping and lighting. The number of streets intersecting at one point should be minimized, and signs and traffic control devices should be adequate to indicate the movements permitted in all traffic lanes. The roadway environment should be simplified and made attractive through screening of distracting and unsightly elements by landscaping, walls and buildings. The clutter of wires, signs and disordered development should be reduced. Conflict between unnecessary private signs and street directional signs should be avoided. Clarity of routes is of similar importance for transit riders. Legible and frequent trafficway signs and an ordered roadway environment will assist these riders. Other improvements should be made in the vicinity of transit stops: these include wider sidewalks, landscaping, lighting and waiting shelters to help identify the stops, and better signs at stops and on vehicles to explain routes, types and frequency of service, and transfer points. POLICY 1.10 Orientation for travel is most effectively provided where there is a citywide system of streets with established purposes: major through streets that carry traffic for considerable distances between districts, local streets that serve only the adjacent properties, and other streets with other types of assigned functions. Once the purposes of streets have been established, the design of street features should help to express those purposes and make the whole system understandable to the traveler. The appropriate purpose of and role for a street in the overall city street network depends on its specific context, including land use and transportation characteristics, and other special conditions. Streets in residential areas must be protected from the negative influence of traffic and provide opportunities for neighbors to gather and interact. Streets in commercial areas must have a high degree of pedestrian amenities, wide sidewalks, and seating areas to serve the multitude of visitors. Streets in industrial areas must serve the needs of adjacent businesses and workers; and so forth. Similarly, busy transportation corridors by necessity carry high volumes and speeds of vehicle traffic, while neighborhood streets have lower speeds and volumes. Hence, the goal for busier corridors should focuses on creating a strong image appropriate to the street’s importance to the city pattern, buffering pedestrians from vehicular traffic, and improving conditions for pedestrians at crossings. The goal for neighborhood streets should be to protect neighborhoods by calming traffic and providing neighborhood-serving amenities. The Better Streets Plan identifies and defines a system of street types and describes the appropriate design treatments and streetscape elements for each street type. Future decisions about the design of pedestrian and streetscape elements should follow the policies and guidelines of the Better Streets Plan, as adopted by the Board of Supervisors on December 7, 2010 and amended from time to time. The Better Streets Plan, is incorporated herein by reference. POLICY 1.11 One type of feature that can be readily adjusted to the street system is landscaping. Accordingly, a plan should be put into effect for street landscaping that indicates the relative importance of streets by the degree of formality of tree planting and the species and size of the trees. In addition to differences in traffic-carrying functions, the plan recognizes the width and visual importance of certain streets, the special nature of various activity areas, and the need for screening or buffering of residential uses along streets carrying heavy traffic. Special consideration is also required for major intersections, and for important views that should not be blocked by landscaping. POLICY 1.12 The same considerations that apply to street landscaping under Policy 10 apply to street lighting as well. A plan similar to that for landscaping should therefore be carried out with respect to lighting, with the design and placement of lighting fixtures and the type of illumination determined by street type and other relevant factors. Human Needs

Natural areas are one such irreplaceable resource. Few examples remain of the original sand dunes, hills, cliffs and beaches that once characterized the peninsula, and fewer still are the examples of natural ecology. Reduction of such areas by development has continued until recent time, and the city can be seen to have reached an irreducible minimum if it is to keep a sense of unspoiled nature for future generations. The natural areas answer human needs for rest, quiet, escape from the city's pace and freedom from confinement. They provide places to view the city from afar, but just as often they can turn the viewer's attention to the secluded interior of the area or to the expanses of the Ocean or the Bay. The Bay is itself a resource of nature, although it has been encroached upon by filling and by barriers that prevent access to much of its present shoreline. Hardly any of the original shoreline remains, but the water of the Bay is still a natural area that can be seen and used by the city's residents as an important part of their lives. The parks and other open spaces developed by man are also resources that change little over time. These areas often approach a natural state, and even as pure open space they would have value for recreation and relief from city congestion. Creation of substantial new open space is both financially and physically difficult, and therefore existing open space has even greater public value as time goes on.

Historic buildings, and in fact nearly all older buildings regardless of their historic affiliations, provide a richness of character, texture and human scale that is unlikely to be repeated often in new development. They help characterize many neighborhoods of the city, and establish landmarks and focal points that contribute to the city pattern. The work of San Francisco's Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board has been notable as a dedicated effort to gain recognition for the city's heritage of older buildings. A number of landmarks have been designated, but many others are threatened and even those designated will not be permanently retained without the cooperation of their owners. Of equal importance to the designation of individual buildings is the recognition and protection of whole block frontages and areas that exemplify early architectural styles and a high quality of design character. The retention of many of the traditions of San Francisco is dependent upon an expansion of preservation efforts in the future. There are other developed areas which, though they may not contain individual buildings that are historic or otherwise outstanding, have a special character worthy of preservation. These areas have an unusually fortunate relationship of building scale, landscaping, topography and other attributes that makes them indispensable to San Francisco's image. Threats to the character of these areas are sure to be met with intense concern by their own residents and by the public at large. The city's streets are a further resource to be conserved. Their value is not merely in the carrying of traffic. Streets are important in perception of the city pattern, since they make visible the city's outstanding features and its points of orientation. Streets also help regulate the organization and scale of building development, spacing out buildings and giving continuity to their facades. Good views are another product of the street system. A majority of the city's streets may be said to have pleasing views of the Bay, the Ocean, distant hills or other parts of the city. Where good views are not available, streets can still function as open space for use by neighborhood residents and for landscaping to bring some sense of nature to the area. Where the intensity of development is high, streets may even be necessary to maintain decent levels of light and air for residents and for pedestrians. In these areas, streets are the "breathing space" that permits buildings to reach high density on private properties. In other functions, streets also carry a complex of utility lines and provide access for truck deliveries and police and fire protection.

With this great variety of public values in the street system, it is necessary that clear policies be established to determine when streets must be retained in their present state, and when, under exceptional circumstances, street areas may be released for other uses consistent with the public interest.

OBJECTIVE 2 If San Francisco is to retain its charm and human proportion, certain irreplaceable resources must not be lost or diminished. Natural areas must be kept undeveloped for the enjoyment of future generations. Past development, as represented both by distinctive buildings and by areas of established character, must be preserved. Street space must be retained as valuable public open space in the tight-knit fabric of the city.

Natural Areas POLICY 2.1 Natural areas in the city that remain in their original state are irreplaceable and must not be further diminished. Significant development should not take place in these areas, and facilities necessary to aid in human enjoyment of them should not disturb their visual feeling or natural ecology. Accordingly, parking lots and service buildings should be confined to areas that are already developed, and access pathways should be designed to have a minimum effect upon the natural environment. Where possible, the interior of these natural areas should be out of sight of the developed city. Lands in public ownership, primarily those of the City and Federal governments, constitute the bulk of these natural areas. Coordinated programs for conservation of both land features and ecology should be carried out, with high priority given to such management functions. Where natural areas are in private ownership, either special incentives or public acquisition should be used to assure a similar degree of preservation. POLICY 2.2 The recreation and open space values of parks and other open and landscaped areas developed by man ought not to be reduced by unrelated or unnecessary construction. These resources are not expected to be increased substantially in future time, whereas the public need for them will surely grow. Facilities placed in these areas should be of a public nature and should add to rather than decrease their recreation and open space values. Facilities that can be accommodated outside of established parks and open spaces should be placed at other appropriate locations. Where new facilities are necessary in these parks and open spaces, they should be sited in areas that are already partially developed in preference to areas with a greater sense of nature. Through traffic, parking lots and major buildings should be kept out of established parks and open spaces where they would be detrimental to recreation and open space values. Parking garages and other facilities should not be placed beneath the surface in these areas unless the surface will retain its original contours and natural appearance. Realignment of existing trafficways in these areas should avoid destruction of natural features and should respect the natural topography with a minimum of cutting and filling. The net effect of any changes in parks and open spaces should be to enhance their visual qualities and beneficial public use. POLICY 2.3 The filling of San Francisco Bay over more than a century has already reduced the size of the Bay and the quality and extent of its natural shoreline below acceptable limits. Further filling and replacement of filled areas should be severely limited to cases in which there are strong public purposes to be served and clear opportunities for increased public use and enjoyment of the Bay and its shoreline. These basic policies have been established on a regional basis by the San Francisco Bay Plan. Development on the Bay shoreline should be related both to the water of the Bay and to the uses and activities that occur inland. Specific plans for sectors of the shoreline adopted by the City should govern the urban design aspects of detailed development, and should emphasize access to the Bay by the city's residents. Access to the Bay should be considered as a total system in which a maximum of communication with the water is made possible consistent with other shoreline uses. Access includes physical contact with the water and the shore at recreation areas, and it also includes visual contact through views of the water and of water-related activities. The system of access requires careful review of development and land use at the water's edge, and similar review of projects further inland that will affect physical and visual contact with the water. Richness of Past Development POLICY 2.4 Older buildings that have significant historical associations, distinctive design or characteristics exemplifying the best in past styles of development should be permanently preserved. The efforts of the Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board should be supported and strengthened, and a continuing search should be made for new means to make landmarks preservation practical both physically and financially. Criteria for judgment of historic value and design excellence should be more fully developed, with attention both to individual buildings and to areas or districts. Efforts for preservation of the character of these landmarks should extend to their surroundings as well. Preservation measures should not, however, be entirely bound by hard-and-fast rules and labels, since to some degree all older structures of merit are worthy of preservation and public attention. Therefore, various kinds and degrees of recognition are required, and the success of the preservation program will depend upon the broad interest and involvement of property owners, improvement associations and the public at large. POLICY 2.5 Although the Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board and other agencies have certain powers relative to the exterior remodeling of designated landmarks, the problem of detrimental remodelings is far broader. The character and style of older buildings of all types and degrees of merit can be needlessly hidden and diminished by misguided improvements. Architectural advice, and where necessary and feasible the assistance of public programs, should be sought in order to assure than the richness of the original design and its materials and details will be restored Care in remodelings should be exercised in both residential and commercial areas. Along commercial streets, the signs placed on building facades must be in keeping with the style and scale of the buildings and street, and must not interfere with architectural lines and details. Compatible signs require the skills of architects and graphics designers. In commercial areas as well as residential neighborhoods, the interest and participation of property owners and occupants should be enlisted in these efforts to retain and improve design quality. POLICY 2.6 Similar care should be exercised in the design of new buildings to be constructed near historic landmarks and in older areas of established character. The new and old can stand next to one another with pleasing effects, but only if there is a similarity or successful transition in scale, building form and proportion. The detail, texture, color and materials of the old should be repeated or complemented by the new. Often, as in the downtown area and many district centers, existing buildings provide strong facades that give continuous enclosure to the street space or to public plazas. This established character should also be respected. In some cases, formal height limits and other building controls may be required to assure that prevailing heights or building lines or the dominance of certain buildings and features will not be broken by new construction. POLICY 2.7 All areas of San Francisco contribute in some degree to the visual form and image of the city. All require recognition and protection of their significant positive assets. Some areas may be more fortunately endowed than others, however, with unique characteristics for which the city is famous in the world at large. Where areas are so outstanding, they ought to be specially recognized in urban design planning and protected, if the need arises, from inconsistent new development that might upset their unique character. These areas do not have buildings of uniform age and distinction, or individual features that can be readily singled out for preservation. It is the combination and eloquent interplay of buildings, landscaping, topography and other attributes that makes them outstanding. For that reason, special review of building proposals may be required to assure consistency with the basic character and scale of the area. Furthermore, the participation of neighborhood associations in these areas in a cooperative effort to maintain the established character, beyond the scope of public regulation, is essential to the long-term image of the areas and the city.

Street Space POLICY 2.8 Street areas have a variety of public values in addition to the carrying of traffic. They are important, among other things, in the perception of the city pattern, in regulating the scale and organization of building development, in creating views, in affording neighborhood open space and landscaping, and in providing light and air and access to properties. Like other public resources, streets are irreplaceable, and they should not be easily given up. Short-term gains in stimulating development, receipt of purchase money and additions to tax revenues will generally compare unfavorably with the long-term loss of public values. The same is true of most possible conversions of street space to other public uses, especially where construction of buildings might be proposed. A strong presumption should be maintained, therefore, against the giving up of street areas, a presumption that can be overcome only by extremely positive and far-reaching justification. POLICY 2.9 Every proposal for the giving up of public rights in street areas, through vacation, sale or lease of air rights, revocable permit or other means, shall be judged with the following criteria as the minimum basis for review: a. No release of a street area shall be recommended which would result in:

b. Release of a street area may be considered favorably when it would not violate any of the above criteria and when it would be:

POLICY 2.10 In order to avoid the unnecessary permanent loss of streets as public assets, methods of release short of total vacation should be considered in cases in which some form of release is warranted. Such lesser methods of release permit later return of the street space to street purposes, and allow imposition of binding conditions as to development and use of the street area. Mere closing of the street to traffic should be used when it will be an adequate method of release. Temporary use of the street should be authorized when permanent use is not necessary. A revocable permit should be granted in preference to street vacation. And sale or lease of air rights should be authorized where vacation of the City's whole interest is not necessary for the contemplated use. In any of these lesser transactions, street areas should be treated as precious assets which might be required for unanticipated public needs at some future time. Human Needs Much of the characteristic pattern of San Francisco has remained the same, and yet change is continuous. New development stands out because it is new and because it is different — sometimes quite different from what the city has known before. The effect upon the pattern of the city and its neighborhoods is often auspicious, but at times it is not. As rebuilding occurs, there may be changes in the city's essential qualities. The fitting in of new development is, in a broad sense, a matter of scale. It requires a careful assessment of each building site in terms of the size and texture of its surroundings, and a very conscious effort to achieve balance and compatibility in the design of the new building. Good scale depends upon a height that is consistent with the total pattern of the land and of the skyline, a bulk that is not overwhelming, and an overall appearance that is complementary to the building forms and other elements of the city. Scale is relative, therefore, since the height, bulk and appearance of past development differ among the districts of the city. People in San Francisco are accustomed to a skyline and streetscape of buildings that harmonize in color, shape and details. Much effort has been made in the past to relate each new building to its neighbors at both upper and lower levels, and to avoid jarring contrasts that would upset the city pattern. Special care has been accorded the edges of distinct districts, where transitions in scale are especially important. By tradition in San Francisco, as in other great cities of the world, unusual building forms and monumental scale have been reserved for buildings with the greatest significance to the community. These buildings characterize the mood and institutions of the city, and by their quality and nature express the city's aspirations to the world at large. In questions of scale, the height of buildings haws received the greatest and most continuous public attention. San Francisco has established the most extensive system of legislated height controls in any American city, expressing its concern over building height in this manner since as early as 1927. Nevertheless, a citywide plan for building height has not existed prior to this time, and both residents and visitors have experienced stress and concern at the prospect that the appearance of the skyline may continue to change rapidly without further direction. Tall buildings are a necessary and expressive form for much of the city's office, apartment, hotel and institutional development. These buildings, as soaring towers in a white city, connote the power and prosperity of man's modern achievements. They make economical use of land, offer fine views to their occupants, and can permit efficient deployment of public services. In recent times, however, new pressures upon the design of these buildings have been produced by increases in technical construction capabilities, in demands for large blocks of floor space, in the breadth of financing methods, and in the image-consciousness of major business firms. As each building becomes larger and the whole city becomes more intensively developed, the challenges for urban design are multiplied. Exceptional height can have either positive or negative effects upon the city pattern and the nearby environment. A building that is well designed in itself will help to reinforce the city's form if it is well placed, but the same building at the wrong location can be utterly disruptive. If properly placed, tall buildings can enhance the topographic form and existing skyline of the city. They can orient the traveler by helping to clarify his route and identify his destination. Building height can define districts and centers of activity. These advantages can be achieved without blocking or reduction of views from private properties, public areas or major roadways, if a proper plan for building height is followed. Such a plan must weigh all the advantages and disadvantages of height at each location in the city, and must take into account appropriate established patterns of building height and scale, seeking for the most part to follow and reinforce those patterns. Such a plan must also be applied with recognition of the functional and economic needs for space in major centers for offices, high density apartments, hotels and institutions providing public services. The remaining aspect of building scale to be considered is that of bulk, or the apparent massiveness of a building in relation to its surroundings. A building may appear to have great bulk whether or not it is of extraordinary height, and the result can be a blocking of near and distant views and a disconcerting dominance of the skyline and the neighborhood. The users of modern building space may find these bulky forms more efficient, and the forms may seem logical for combining several uses in a single development, but such considerations do not measure the external effects upon the city. Neither height limits nor limits upon the amounts of floor space permitted will directly control excessive bulk, and therefore specific attention to this problem is called for. The apparent bulk of a building depends primarily upon two factors: the amount of wall surface that is visible, and the degree to which the structure extends above its surroundings. Accordingly, a plan seeking to avoid excessive bulkiness must consider the existing scale of development in each area of the city and the effects of topographic form in exposing building sites to widespread view. The largest potential building sites present the greatest problems and challenges for moderation of building form. On these sites, normal controls over the form and intensity of construction that are intended primarily for smaller sites have less precision, and the external effects of large developments upon the surrounding area and upon the city may be far greater. The stakes are high for both the developers and the future of the city, with a resulting tendency toward controversy and frustration, and unfortunate divisive effects in the community. For these reasons, the larger sites require separate and more intensive consideration in policies relating to building form. OBJECTIVE 3

As San Francisco grows and changes, new development can and must be fitted in with established city and neighborhood patterns in a complementary fashion. Harmony with existing development requires careful consideration of the character of the surroundings at each construction site. The scale of each new building must be related to the prevailing height and bulk in the area, and to the wider effects upon the skyline, views and topographic form. Designs for buildings on large sites have the most widespread effects and require the greatest attention.

Visual Harmony POLICY 3.1 New buildings should be made sympathetic to the scale, form and proportion of older development. This can often be done by repeating existing building lines and surface treatment. Where new buildings reach exceptional height and bulk, large surfaces should be articulated and textured to reduce their apparent size and to reflect the pattern of older buildings. Although contrasts and juxtapositions at the edges of districts of different scale are sometimes pleasing, the transitions between such districts should generally be gradual in order to make the city's larger pattern visible and avoid overwhelming of the district of smaller scale. In transitions between districts and between properties, especially in areas of high intensity, the lower portions of buildings should be designed to promote easy circulation, good access to transit, good relationships among open spaces and maximum penetration of sunlight to the ground level. In new, high-density residential areas near downtown where towers are being contemplated as part of comprehensive neighborhood planning efforts, such as Transbay and Rincon Hill, such towers should be slender and widely spaced among buildings of lesser height to allow ample sunlight, sky exposure and views to streets and public spaces. It is thus to be expected that some tall buildings will be located adjacent to buildings of significantly lower height. This, does not in itself, create disharmony or poor transitions, but is in fact necessary in order to achieve important neighborhood-wide livability goals. Because these areas are on the edges of the downtown, stricter standards than exist in the downtown core for tower bulk and spacing should be established to minimize the bulk of towers and set minimum tower spacing. It is especially important that towers have active ground floors and that lower stories are highly articulated and engage the pedestrian realm, with multiple building entrances, townhouses, retail, and neighborhood services. (See Map 4.) POLICY 3.2 Large buildings are most consistent with the visual unity of the city when they are light in color. The characteristics of San Francisco's climate and the varied effects of sunlight through the day in clear and fog-filled skies make bright but subtle hues a life-giving element in the skyline. Prominent new buildings should reflect this pattern. Buildings of unusual shape stand out in the skyline. They call attention to themselves and correspondingly reduce the visual significance of other features in the city pattern. Such buildings may also create a jarring disharmony that counteracts the traditional blending of regular rectilinear forms in the San Francisco skyline. Unusual shapes, especially in large buildings, should therefore be reserved for structures of broad public significance such as those providing community-wide services. POLICY 3.3 Certain buildings will achieve prominence, whatever their design, because of their exposed locations. Among such locations are those at tops of hills; those fronting on permanent open space such as the Bay, parks, plazas and areas with height limits; those facing wide streets or closing the vista at the end of a street; and those affording a silhouette against the sky, a muted background or a formal order such as in the Civic Center. At locations of such prominence, the quality of building design is of special significance, and special efforts should be made to promote the best architectural solutions in both public and private buildings. In such solutions, the positive potentials of the site should be emphasized. Height and Bulk POLICY 3.4 New buildings should not block significant views of public open spaces, especially large parks and the Bay. Buildings near these open spaces should permit visual access, and in some cases physical access, to them. Buildings to the south, east and west of parks and plazas should be limited in height or effectively oriented so as not to prevent the penetration of sunlight to such parks and plazas. Larger squares and plazas will benefit, in addition, from uniform facade lines and cornice heights around them which will visually contain the open space. Large buildings and developments should, where feasible, provide ground level open space on their sites, well situated for public access and for sunlight penetration. The location and dimensions of such open space should be carefully considered with respect to the placement of other buildings and open spaces in the area, and with respect to the siting and functioning of the building with which it is provided. Where separation of pedestrian and vehicular circulation levels is possible in provision of such open space, such separation should be considered. POLICY 3.5 The height of new buildings should take into account the guidelines expressed in this Plan. These guidelines are intended to promote the objectives, principles and policies of the Plan, and especially to complement the established city pattern. They weigh and apply many factors affecting building height, recognizing the special nature of each topographic and development situation. Tall, slender buildings should occur on many of the city's hilltops to emphasize the hill form and safeguard views, while buildings of smaller scale should occur at the base of hills and in the valleys between hills. In other cases, especially where the hills are capped by open spaces and where existing hilltop development is low and small-scaled, new buildings should remain low in order to conserve the natural shape of the hill and maintain views to and from the open space. Views along streets and from major roadways should be protected. The heights of buildings should taper down to the shoreline of the Bay and Ocean, following the characteristic pattern and preserving topography and views. Tall buildings should be clustered downtown and at other centers of activity to promote the efficiency of commerce, to mark important transit facilities and to avoid unnecessary encroachment upon other areas of the city. Such buildings should also occur at points of high accessibility, such as rapid transit stations in larger commercial areas and in areas that are within walking distance of the downtown's major centers of employment. In these areas, building height should taper down toward the edges to provide gradual transitions to other areas. In areas of growth where tall buildings are considered through comprehensive planning efforts, such tall buildings should be grouped and sculpted to form discrete skyline forms that do not muddle the clarity and identity of the city's characteristic hills and skyline. Where multiple tall buildings are contemplated in areas of flat topography near other strong skyline forms, such as on the southern edge of the downtown "mound," they should be adequately spaced and slender to ensure that they are set apart from the overall physical form of the downtown and allow some views of the city, hills, the Bay Bridge, and other elements to permeate through the district. In residential and smaller commercial areas, tall buildings should occur closest to major centers of employment and community services which themselves produce significant building height, and at locations where height will achieve visual interest consistent with other neighborhood considerations. At outlying and other prominent locations, the point tower form (slender in shape with a high ratio of height to width) should be used in order to avoid interruption of views, casting of extensive shadows or other negative effects. In all cases, the height and character of existing development should be considered. The guidelines in this Plan express ranges of height that are to be used as an urban design evaluation for the future establishment of specific height limits affecting both public and private buildings. For any given location, urban design considerations indicate the appropriateness of a height coming within the range indicated. The guidelines are not height limits, and do not have the direct effect of regulating construction in the city. POLICY 3.6 When buildings reach extreme bulk, by exceeding the prevailing height and prevailing horizontal dimensions of existing buildings in the area, especially at prominent and exposed locations, they can overwhelm other buildings, open spaces and the natural land forms, block views and disrupt the city's character. Such extremes in bulk should be avoided by establishment of maximum horizontal dimensions for new construction above the prevailing height of development in each area of the city. The guidelines for building bulk expressed in this Plan are intended to form an urban design basis for such regulation. These guidelines favor relatively slender construction above prevailing heights, but would not limit the horizontal dimensions of buildings below those heights. Generally speaking, the guidelines would not limit the total floor space that could be built, but would help to shape it to avoid negative external effects. If two or more towers are to be built on a single property, their total effect should be considered and a significant separation should be required between them. The precise form of the building or buildings would in large measure be left to the individual developer and his architects under these guidelines. The guidelines of this Plan for building bulk are only minimum guidelines, and they are not intended to reduce the necessity for other expressed policies pertaining to height, visual harmony or other factors. Even with building bulk kept within these guidelines, efforts should be made to articulate and soften building surfaces to reduce the massiveness of appearance to a great degree.

MAXIMUM PLAN DIMENSION: The greatest horizontal dimension along any wall of the building, measured at a height corresponding to the prevailing height of other development in the area.

MAXIMUM DIAGONAL PLAN DIMENSION: The horizontal dimension between the two most separated points on the exterior of a building, measured at a height corresponding to the prevailing height of other development in the area. Large Land Areas POLICY 3.7 The larger a potential site for development, the greater are apt to be the size and variety of the urban design questions raised. Larger sites may mean greater visual prominence of development and greater impact upon the city pattern. As more land area is included in a single project, the possibilities are increased that the public resources in natural areas, historic buildings and street space will be affected. Larger developments also have substantial requirements for public services, including transportation. Under normal land use controls, most large development is governed by a "floor area ratio", which permits floor space to be built in each project in proportion to the amount of land area available. The floor area ratio limit tends to be geared to development of sites of small and moderate size, but not to take account of the impact of occasional developments that take up one or more whole blocks of land. Such developments, under this type of formula, may have a single building of truly massive proportions, or a series of building forms constructed in one or more phases. These differences in nature and impact require that large sites be given close consideration in urban design planning. POLICY 3.8 The height and bulk guidelines of this Plan will help to some extent in reducing the negative effects of development on large sites. They will not, however, deal with all the special problems raised or guarantee good quality of design. Other measures are available and may be necessary. In some cases, ordinary zoning restrictions might be tightened, or rezoning to permit a large development might be deferred in the absence of adequate assurances of compatible development. New standards might be added to require open space in large projects, and floor area ratios might be reduced or made less advantageous for larger sites. Because government involvement often occurs as larger sites are developed, through marketing of the site itself, through redevelopment powers, through vacation of streets or in some other manner, the government role might be made more restrictive in such involvement. There is no substitute, however, for early and frequent communication as to the merits and design of a proposed project between the developer and his architects on the one hand and public urban design professionals and interested citizens on the other. Such communication will give an early and more reasoned assessment of the positive and negative effects of the project upon the city and the surrounding area, and will reduce the chances of later delays and controversies. Processes toward these ends should be employed for all major projects in the city. POLICY 3.9 Development of large properties, by condensing growth and change in certain areas of the city, emphasizes the effects that long-term growth and change can have upon the physical makeup of San Francisco. There is nothing in the nature of cities that will guarantee the continued livability of this or any other city. The citizens of San Francisco have an uncommon awareness that the environment is finite, and that the advantages of greater size and intensity may have ultimate limits. That awareness is healthy and progressive and should be fostered. It should be given new outlets to help shape the physical form of the city. As in this Urban Design Plan, it can identify the attributes of the city that need to be protected and enhanced. Good planning, supported by an interested public, can channel growth to the right places in the city, build growth around previously established transportation systems and other services, cause other public costs to be borne in part by the developers who benefit from them, and hold in place the natural regulators of growth such as streets and open spaces. Above all, it can and should control the form of individual buildings so that they will be compatible with the character of the city. More should be known as to the long term effects of growth in San Francisco. These effects and the means for moderating them should be studied in a rational manner through the normal processes of planning, and none of the important factors should be overlooked. Ultimately, certain limits upon total growth may prove to be necessary if the integrity of the city is to be preserved. Human Needs The people of San Francisco are the city's reason for being and its hope for the future. Most residents live in areas that can be characterized as distinct neighborhoods, and the quality of these neighborhoods has a strong effect upon their personal outlook. Neighborhood quality is of overriding importance to the individual, since the most basic human needs must be satisfied close to home. The long-term future of the city's entire physical environment may also depend upon good neighborhoods, because only when they find satisfaction in their own areas can residents freely turn their attention to matters affecting the larger community. There is no great difference of opinion as to what makes a neighborhood a good place to live from an urban design standpoint: people wish to have a tolerable and comfortable living environment, safe and free from stress, and the elements that make up such an environment are easily described. People also wish to know that their neighborhoods will be guarded against physical deterioration, and that any elements they consider deficient are likely to be improved. Because neighborhood quality is defined in the residents' own terms, the neighborhood environment will be better if residents participate in the planning of local improvements. Studies show that the outstanding concerns of people today in their neighborhood environment are matters of health and safety. Traffic is the leading issue, with automobiles moving through residential areas in large volumes and at high speeds, producing noise and pollutants and putting pedestrians in constant danger. With each increase in traffic the streets become less a part of the living environment and more a world of their own. Residents find the streets unsafe and unpleasant, and try to shut them out. The quality of neighborhood maintenance is also of major concern. A sense of pride and satisfaction requires that all parts of the local environment be well maintained: streets, parks, public buildings, neighbors' properties, and especially one's own house and yard. When the area is well kept and has visual qualities that distinguish it from other areas, a resident has a feeling of neighborhood that gives him a sense of being at home though he may be a block or more from his dwelling. Another element of good neighborhoods is the presence of open space and recreation opportunities. The most satisfying recreation space is close by and visible, with a feeling of nature and a variety of facilities for all age groups. Such recreation space may be found on private properties, in neighborhood parks, along the sidewalks and in undeveloped street areas. On a citywide scale, larger recreation facilities that require travel away from home provide an even greater variety of opportunities. On this larger scale, the shoreline of San Francisco Bay has a potential that is not fully used. There are many other elements that can bring amenity to the neighborhood environment. Planting in streets and yards, well designed and well cared for, adds immeasurably to the visual quality of an area, softening and complementing the hard appearance of pavement and buildings. Continuous building facades and generous sidewalks with interesting details establish a pleasant mood for the pedestrian. Freedom from the clutter of open parking lots, large signs and overhead wires can also make the difference between an agreeable living environment and one that is disquieting or even blighted. With respect to the many improvements in environment that can be made by public and private actions, the needs of the city's neighborhoods are by no means uniform. Some neighborhoods have serious deficiencies in one or more elements affecting neighborhood quality, while others are more fortunate. Some neighborhoods have greater needs because their residents live in conditions of greater density, or because the residents include more children and older people who tend to live within a smaller world in which the resources close at hand are the most important. People of low income, too, especially renters who have little direct role in maintaining their own physical environment, have special needs that characterize certain neighborhoods where the danger of physical decline is already very apparent. These differences in neighborhoods point up the need to establish priorities in the programs that will stabilize and improve the local environment. Where serious physical deficiencies already exist, and where the density, age and economic status of residents indicate special needs, the neighborhoods require immediate and continuing assistance. Of equal importance, however, are many other areas that may be on the verge of physical decline. These other areas require priority because the residents' fear of change may contribute as much as any other factor to real deterioration, and such fear can be overcome by visible efforts to stabilize the neighborhood. Once lost, the existing resources in any neighborhood can be restored only through great expense and dislocation. The programs relating to neighborhood environment should, therefore, be designed both to hold neighborhood quality at its present levels and to improve deficient areas that do not enjoy the fine attributes of other parts of San Francisco. OBJECTIVE 4 San Francisco draws much of its strength and vitality from the quality of its neighborhoods. Many of these neighborhoods offer a pleasant environment to residents of the city, while others have experienced physical decline and still others have never enjoyed some of the amenities common to the city as a whole. Measures must be taken to stabilize and improve the health and safety of the local environment, the psychological feeling of neighborhood, the opportunities for recreation and other fulfilling activities, and the small-scale visual qualities that make the city a comfortable and often exciting place in which to live.

POLICY 4.1 In order to reduce the hazards and discomfort of traffic in residential neighborhoods, a plan for protected residential areas should be put into effect. Such a plan is intended to prevent or discourage heavy, fast and through traffic from using residential streets, and to put such traffic on arterial streets where the impact upon residential areas will be less disruptive. Although development of further traffic-carrying capacity on some arterials may be warranted, the local streets should remain as they are or have their capacity reduced.

Land uses throughout the city should be regulated in such a way that heavy traffic will not be drawn through protected streets by large commercial, industrial and institutional traffic generators. Traffic for these generators should be channeled as much as possible on arterial streets. High traffic speeds should be discouraged on non-residential streets where the traffic on those streets is destined for protected residential streets. POLICY 4.2 When arterials and other streets having heavy traffic must go through residential areas, steps should be taken to screen dwellings from the noise, fumes and other adverse effects of traffic. Heavy landscaping at the sides of streets and in center islands may provide an effective barrier, as can walls, differences in elevation and the setting back of dwellings from the roadways. Dwellings along streets with heavy traffic should, where possible, have the main orientation of their living space and access away from the traffic. In some cases further measures such as soundproofing may be required. Business and industries that attract or produce heavy traffic, such as service stations and trucking terminals, should be screened from nearby residential areas. Screening should be provided, as well, for all open parking lots within or adjacent to residential areas. All of the aforementioned considerations should apply to recreation areas as well as to dwellings.

POLICY 4.3 In order to reduce the hazards of traffic at night, and to provide security from crime and other dangers, public areas should have adequate lighting. Although the need for lighting is general, special attention should be given to crosswalks and to pathways in parks and around public buildings. Care should be taken to shield the glare of any such lighting from residential properties. POLICY 4.4 Pedestrian walkways should be sharply delineated from traffic areas, and set apart where possible to provide a separate circulation system. Where necessary and practical, the separation should include landscaping and other barriers, and walkways should pass through the interiors of blocks. Walkways that cross streets should have pavement markings and good sight distances for motorists and pedestrians. Driveways across sidewalks should be kept to a practical minimum, with control maintained over the number and width of curb cuts. Barriers should be installed along parking lots to avoid encroachments on sidewalks, with adequate sight distances maintained at driveways. Truck loading should occur on private property rather than in roadways or on the sidewalks, and sidewalk elevators should be discouraged. Residential parking should be as close as possible to the dwelling served, with adequate lighting along the walking route from the parking to the dwellings. Feeling of Neighborhood POLICY 4.5 In view of the importance attached to the cleaning, paving and other maintenance of streets as an index of neighborhood upkeep, and as a stimulant to private improvements, these types of programs should be carried on continuously and effectively. The same degree of maintenance should be accorded to parks, buildings and other public facilities. In both the initial design and the upkeep of these facilities, the image of government and of its role in the community should be made attractive and inviting. Special attention should be given to the landscaping of public buildings. POLICY 4.6 Local centers for shopping, government services and congregation of people should stand out in their areas. Landscaping, distinctive pavement and other features will help to emphasize these centers. Along shopping streets pedestrian interest should be maintained by continuous store frontages. Government services for the local area, such as offices and libraries, should occupy the same center as the commercial activities. POLICY 4.7 Neighborhood participation in programs for the physical improvement of residential and shopping areas assures an additional measure of pride and satisfaction in the results, and helps to stimulate continuous maintenance of the improvements. Such stimulation of neighborhood interest may be unnecessary or more drastic action for upgrading of the area at some future time. Programs that can make use of both voluntary work and government assistance include street tree planting and development of small parks and other recreation facilities. Where possible, significant public improvements in street areas should be accompanied by financial and design assistance to property owners under programs such as the Federally Assisted Code Enforcement Program which assure the coordinated upgrading of an entire neighborhood. Opportunity for Recreation POLICY 4.8 As many types of recreation space as possible should be provided in the city, in order to serve all age groups and interests. Some recreation space should be within walking distance of every dwelling, and in more densely developed areas some sitting and play space should be available in nearly every block. The more visible the recreation space is in each neighborhood, the more it will be appreciated and used. Recreation space at a greater distance should be easily accessible by marked driving routes, and where possible by separated walkways and bicycle paths. Larger recreation areas should be highly visible. San Francisco Bay is included among the major recreation resources of the city, and visual and physical access to the Bay should be increased, with a maximum interface of land and water made available in new developments having public access. All possible means of providing recreation facilities should be explored. Some historic buildings and their sites have such a potential. Many commercial areas have a semi-recreational aspect, and this aspect should be recognized and strengthened. Where possible, new facilities such as parking garages in more intensively developed parts of the city should have recreation space placed above them. POLICY 4.9 Parks provide their greatest service to the community when they bring a sense of nature to city residents. Recreation facilities suited to each park and its neighborhood should be installed and maintained, while facilities not primarily intended for recreation or not requiring a park location should be placed outside the park system. Automobile traffic in parks should be minimized, and where possible means of transportation other than automobiles should be provided in larger parks. Automobile parking should occur at the edges of parks, preferably outside the park boundaries. Parking lots and other visually distracting uses should be screened from the areas devoted to recreation. POLICY 4.10 As the city grows more intensive, much of the new area for recreation will have to be provided on private property, whether for individual developments or for the public at large. This recreation space may be of many types. Recreation space should be provided in large developments, especially in areas of high population and building density. In the downtown area, well-designed plazas with public access and good exposure to sunlight serve this function. In apartment developments, some of the recreation needs of the occupants should be satisfied on the site itself, if necessary by joint use of space by several properties in the block. New developments along the shoreline of the Bay should whenever possible provide recreation space or general public access to the Bay. POLICY 4.11 Walking along neighborhood streets is the common form of recreation. The usefulness of streets for this purpose can in many cases be improved by widening sidewalks and installing simple improvements such as benches and landscaping. Such improvements can often be put in place without narrowing traffic lanes by use of parking bays with widened sidewalks at intersections and at other points unsuitable for parking. Streets that have roadways wider than necessary, and streets that are not developed for traffic because of their steepness, provide exceptional opportunities for recreation. This is particularly applicable in new neighborhoods like Transbay and Rincon Hill, where traditional open spaces are more difficult to assemble because of higher densities and lack of available sites to acquire for parks. This excess street space can be developed with playgrounds, sitting areas, viewpoints and landscaping that make them neighborhood assets and increase the opportunities for recreation close to the residents' homes. Visual Amenity POLICY 4.12 Trees and other landscaping are a recurring theme in these policies, for they add to nearly any city environment. Both public and private efforts in the installation and maintenance of landscaping should be increased. In residential areas, side yards and setbacks provide the best opportunities for landscaping visible in public areas. If no such space exists, then trees should be placed in the sidewalk area, preferably in the ground. Care should be taken to select species of trees suitable to each location. The most visible points, such as street intersections, should be given special attention. Other unused opportunities for landscaping exist on exposed banks, usually along roadways. Where it is feasible, these should be planted and maintained by the public or private owners of the land. Portions of parks that are unlandscaped should also be considered for new planting, especially when the areas are visible from nearby neighborhoods. POLICY 4.13 In addition to landscaping, other features along the streets add to the comfort and interest of pedestrians. Sidewalk paving and furnishings, if designed in a unified way, make walking more pleasurable. Gentle changes in level have the same effect. In commercial areas, continuous and well-appointed shop windows and arcades are invitations to movement. Little-used alleys can be improved as walkways, and new promenades put through blocks in new development. Greater comfort should also be provided at transit stops, where benches and shelters can be placed on sidewalks and on private property. POLICY 4.14 No other element in the street environment is more disrupting than exposed parking. Parking lots and open parking decks break the building facades and stand as large voids in visual interest. Exposed vehicles clutter the pedestrian's view and reduce the sidewalk to a narrow corridor between rows of automobiles. Parking should, wherever possible, be placed beneath or behind buildings or else screened from view by landscaping, walls or fences. The screening should be designed to restore to the street some of the visual interest that has been taken away by the removal of buildings. Signs are another leading cause of street clutter. Where signs are large, garish and clashing they lose their value as identification or advertising and merely offend the viewer. Often these signs are overhanging or otherwise unrelated to the physical qualities of the buildings on which they are placed. Signs have an important place in an urban environment, but they should be controlled in their size and location. Other clutter is produced by elements placed in the street areas. The undergrounding of overhead wires should continue at the most rapid pace possible, with the goal the complete elimination of such wires within a foreseeable period of time. Every other element in street areas, including public signs, should be examined with a view toward improvement of design and elimination of unnecessary elements. POLICY 4.15 Whatever steps are taken in the street areas, they may be lost in the changed atmosphere produced by new buildings. Human scale can be retained if new buildings, even large ones, avoid the appearance of massiveness by maintaining established building lines and providing human scale at their lower levels through use of texture and details. If the ground level of existing buildings in the area is devoted to shops, then new buildings should avoid breaking the continuity of retail space. In residential areas of lower density, the established form of development is protected by limitations on coverage and requirements for yards and front setbacks. These standards assure provision of open space with new buildings and maintenance of sunlight and views. Such standards, and others that contribute to the livability and character of residential neighborhoods, should be safeguarded and strengthened. This Urban Design Plan for San Francisco has been developed with the conviction that quality in the urban environment is an important and growing concern in this great city. The people of San Francisco have taken a leadership role among the citizens of the country in balancing conservation and change through new safeguards for cherished attributes of their city's character. This Plan is intended to reflect the people's needs and to improve the physical makeup of the city. As new needs and concerns arise in later years, this Plan will be added to and revised in the continuing process of comprehensive planning.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

© City & County of San Francisco. All rights reserved. |

The

agreeable pattern of San Francisco's appearance is, perhaps above all,

what makes this a city with feeling. The pattern is a visual framework

composed of the natural base upon which the city rests, together with

man's development. In some ways the pattern is seen in two dimensions

as though it were a map; in other ways it has a sculptural or three-dimensional

form.

The

agreeable pattern of San Francisco's appearance is, perhaps above all,

what makes this a city with feeling. The pattern is a visual framework

composed of the natural base upon which the city rests, together with

man's development. In some ways the pattern is seen in two dimensions

as though it were a map; in other ways it has a sculptural or three-dimensional

form. People

perceive this pattern from many places and during many activities; from

their homes and neighborhoods, from parks and the shoreline during recreation,

from places of work, from the streets while traveling, and from entranceways

and observation points while visiting the city.

People

perceive this pattern from many places and during many activities; from

their homes and neighborhoods, from parks and the shoreline during recreation,

from places of work, from the streets while traveling, and from entranceways

and observation points while visiting the city. Two

of the controllable elements that help strengthen the city pattern are

visually prominent landscaping and street lighting. Because these elements

can be so easily affected in a positive way by human actions, and especially

by programs of the City government, they are given important attention

in the policies of this Element. Opportunities for use of these elements

are by no means fully realized now, and systems for landscaping and lighting

are incomplete. As a consequence, parts of the city pattern that otherwise

would be easily read are unclear, and the functions of the street system

are apt to be confused both by day and at night. In addition, some areas

of the city are favored by the amenities produced by good landscaping

and lighting systems while others are not.

Two

of the controllable elements that help strengthen the city pattern are

visually prominent landscaping and street lighting. Because these elements

can be so easily affected in a positive way by human actions, and especially

by programs of the City government, they are given important attention

in the policies of this Element. Opportunities for use of these elements

are by no means fully realized now, and systems for landscaping and lighting

are incomplete. As a consequence, parts of the city pattern that otherwise

would be easily read are unclear, and the functions of the street system

are apt to be confused both by day and at night. In addition, some areas

of the city are favored by the amenities produced by good landscaping

and lighting systems while others are not.

In

the intensely urban environment of San Francisco, there are things that

have not changed. These features provide people with a feeling of continuity

over time, and with a sense of relief from the crowding and stress of

city life and modern times. As the city grows, the keeping of that which

is old and irreplaceable may be as much a measure of human achievement

as the building of the new. Certainly, the old should not be replaced

unless what is new is better.

In

the intensely urban environment of San Francisco, there are things that

have not changed. These features provide people with a feeling of continuity

over time, and with a sense of relief from the crowding and stress of

city life and modern times. As the city grows, the keeping of that which

is old and irreplaceable may be as much a measure of human achievement

as the building of the new. Certainly, the old should not be replaced

unless what is new is better. Older

buildings, too, lend a sense of permanence and pleasant contrast. They

are links with past history, and with earlier styles of development and

of living. Buildings that endure maintain a continuous culture and may

set standards of excellence with which contemporary development can be

compared. In some cases certain buildings may be identified with specific

people or events or with great architects. Such buildings are resources