|

|

| Planning Home > General Plan > Market and Octavia Area Plan

Market and Octavia Area Plan

The Market and Octavia Area Plan (The Plan) grew out of the Market and Octavia Neighborhood Plan (Neighborhood Plan) that in turn was the first plan to emerge from the Better Neighborhoods Program. This Area Plan is a summary of the topics covered in the neighborhood plan The neighborhood plan was also adopted by the Planning Commission and should be referred to for further details and illustrations. As one of three neighborhoods in the Better Neighborhoods Program, the Market and Octavia neighborhood offers a distinct set of opportunities for change sensitive to existing patterns, given its unique place in the city and the region. At the center of the city, it sits at a remarkable confluence of city and regional transportation. It is accessible from the entire Bay Area by BART and the regional freeway system. More than a dozen transit lines cross the Market and Octavia neighborhood, including all of the city’s core streetcar lines, which enter the downtown here. It is just west of the Civic Center, where City Hall and state and federal office buildings, Herbst Theatre, and other governmental and cultural institutions attract a wide range of people both day and night. The Market and Octavia neighborhood sits at the junction of three of the city’s grid systems. The north of Market, south of Market, and Mission grids meet at Market Street, creating a distinct pattern of irregular blocks and intersections, and bringing traffic from these grids to Market Street. The surrounding topography of the Western Addition, Nob Hill, Cathedral Hill, and Twin Peaks flattens out in this area, creating a geography that makes the Market and Octavia neighborhood a natural point of entry to the downtown from the rest of the city. As a result of its central location, it has long been both a crossroads—a place that people pass through—as well as a distinctive part of the city in its own right. The Market and Octavia neighborhood is a truly urban place, with a diversity of character and quality in its various parts. Local residents will tell you that the area is an “in-between ” place—a place that supports a variety of lifestyles, ages, and incomes. Its varied but close-knit pattern of streets and alleys, along with relatively gentle topography, make it very walkable and bikeable. It has excellent access to city and regional public transit and offers a good variety of commercial streets that provide access to daily needs. It has a rich pattern of land uses that integrates a diversity of housing types, commercial activities, institutions, and open spaces within a close-knit physical fabric. The Market and Octavia neighborhood’s strengths as an urban place, an exciting “in-between” place, are fragile. Its role as a crossroads poses enormous challenges. Over the past 100 years, the imposition of large infrastructure and redevelopment projects have deeply scarred the area’s physical fabric. Whole city blocks were assembled for large redevelopment projects in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Large flows of automobile traffic are channeled through to the Central Freeway via major arteries such as Fell/Oak, Gough/Franklin, and Van Ness Avenue. Street management practices meant to expedite these traffic flows have degraded the quality of its public spaces and conflicts between cars and pedestrians have made streets hostile to public life. Because large flows of automobile traffic and core transit lines converge here, there are competing needs for a limited amount of street space. Transit vehicles are often stuck in traffic, impacting transit service and reliability citywide and adding to traffic congestion. Parking requirements have led to buildings in recent years with long, dead, and undifferentiated facades that diminish the quality of the streets. At the same time, there are tremendous opportunities for positive change in the Market and Octavia neighborhood—opportunities to build on its strengths as an urban place and to create a better future. The Market and Octavia neighborhood is undergoing dramatic renewal since the Central Freeway was removed north of Market Street. With the passage of Proposition E in 1998, construction of a graceful and functional surface boulevard has replaced the structure and has freed-up over 7 acres of land for infill development that will help repair the divisions created by the Central Freeway. As part of this effort, there is an opportunity to rationalize regional traffic flows and minimize their negative effects on the quality of life of the area, as well as to plan for the reuse of several other large sites. The Market and Octavia neighborhood can grow supported by its access to public transit. In addition to repairing its physical fabric, new development can take advantage of the area’s rich transit access to provide new housing and public amenities, and reduce new traffic and parking problems associated with too many cars in the area. Because the Market and Octavia neighborhood’s location supports a lifestyle that doesn’t have to rely on automobiles, space devoted to moving and storing them can be dramatically reduced—allowing more housing and services to be provided more efficiently and affordably. Market and Octavia can capture the benefits of new development while minimizing the negative effects of more automobiles. If planned well, new development will strengthen and enhance the Market and Octavia neighborhood. With the removal of the Central Freeway and construction of the new Octavia Boulevard, there is a strong desire here to repair damage done in past decades and realize its full potential as a vibrant urban place. There is potential for new mixed-use development, including a significant amount of new housing. With the added vitality that new housing and other uses will bring, the area’s established character as an urban place can be strengthened and enhanced. The Market and Octavia neighborhood is at a critical juncture. Over the last 40 years, an imbalance in how we plan for the interrelated needs of housing, transportation, and land use has undermined our ability to provide housing and services efficiently, to provide streets that are the setting for public life, and to build on transit, bicycling, and walking as safe and convenient means of getting around our city. Nowhere is this imbalance clearer than here, where an elevated freeway, land assembly projects, and other well-meaning interventions have degraded the overall quality of the place. As we look forward, there is much that can be done. The Plan aims, above all, to restore San Francisco’s long-standing practice of building good urban places—providing housing that responds to human needs, offering people choice in how they get around, and building “whole” neighborhoods that provide a full range of services and amenities close to where people live and work. To succeed, The Plan need only learn from the established urban structure that has enabled the Market and Octavia neighborhood, like other urban places, to work so well for people over time. If the Market and Octavia neighborhood’s tradition of public activism on these issues is any indication, this Area Plan will succeed by building on these strengths: enriching its critical mass of people and activities, enhancing the area’s close-knit physical pattern, and investing in a transportation program that restores balance between travel modes. The Plan addresses these issues holistically, as success with any one aspect depends on addressing the overall dynamic between them. To diminish any one aspect of The Plan is to diminish the opportunity presented by the whole.

Strengthening the Market and Octavia area requires a comprehensive approach to planning for all aspects of what makes the place work well for people. Housing alone does not make a place, although new housing, and the people it brings, will add life to the area. Providing adequate and appropriate space for a range of land uses that contribute to the function, convenience, and vitality of the place are encouraged as part of an integrated land use and urban design vision for the area. Land Use To reinforce and improve on the existing land use pattern, this plan establishes the following principles:

Significant change is envisioned for the “SoMa West” area, which lies between Market Street, South Van Ness Avenue, Mission Street and the Central Freeway. For more than three decades the city’s General Plan has proposed that this area become a mixed-use residential neighborhood adjacent to the downtown. This element of the plan carries this policy forward by encouraging relatively high-density mixed-use residential development in the SoMa West area. Element 7, “A New Neighborhood in SoMa West,” proposes an bold program of capital improvement to create a public realm of streets and open spaces appropriate for the evolution of the public life of the area, and to serve as the catalyst for the development of a new mixed-use residential neighborhood. Urban Form The urban form and height proposals in this plan are based on the existing built form of the area and its surroundings, as follows:

OBJECTIVE 1.1 The new land use and special use districts, along with revisions to several existing districts, implement this concept. These land use districts provide a flexible framework that encourages new housing and neighborhood services that build on and enhance the area’s urban character. Several planning controls are introduced, including carefully prescribed building envelopes and the elimination of housing density limits, as well as the replacement of parking requirements with parking maximums, based on accessibility to transit.

See Map 1. Land Use Districts and Figure 3. Zoning District Table

POLICY 1.1.1 With the removal of the Central Freeway and construction of Octavia Boulevard, approximately 7 acres of land has been made available for new development. Appropriate use and careful design of development on the former freeway lands will repair the urban fabric of Hayes Valley and adjacent areas. New development should conform with the neighborhood’s existing urban scale and character, and should maintain a strong connection to streets and public spaces. POLICY 1.1.2 In keeping with the plan’s goal of prioritizing the safe and effective movement of people, the most intense uses and activities are focused where transit and walking are most convenient and attractive—along the Market Street / Mission Street corridor and at the intersection of Market Street and Van Ness Avenue. Concentrating transit-oriented uses in these locations will reduce automobile traffic on city streets and support the expansion of transit service in the area’s core urban center. POLICY 1.1.3 There are significant opportunities for new mixed-use infill along neighborhood commercial streets in the plan area. In conjunction with proposals to encourage flexible housing types and to reduce parking requirements, new development along commercial streets should create new retail uses and services oriented to the street, with as much housing as possible on upper floors. New uses should maintain the overall pedestrian orientation of these streets. POLICY 1.1.4 There is a demonstrated need for neighborhood-serving uses in the SoMa West area. As its residential population increases, adequate space for retail activities and other services are encouraged as part of the overall mix of uses in the area. While some amount of office uses will be permitted, it will not be allowed to dominate the ground floor in areas where significant new housing is proposed. POLICY 1.1.5 Market Street has historically been the city’s most important street. New uses along Market Street should respond to this role and reinforce its value as a civic space. Ground-floor activities should be public in nature, contributing to the life of the street. High-density residential uses are encouraged above the ground floor as a valuable means of activating the street and providing a 24-hour presence. A limited amount of office use is permitted in the Civic Center area as part of the overall mix of activities along Market Street. POLICY 1.1.6 Major cultural institutions such as City Hall, the Opera House, Herbst Theatre, and the SFLGBT Community Center are vital assets adjacent to the neighborhood and will retain their role as major regional destinations. POLICY 1.1.7 In recent years, Upper Market Street has housed commercial space to important community-serving organizations offering aid for homeless, disadvantaged and/or those with special health needs. In part, this has been made possible due to the relatively low commercial rents. With the removal of the Central Freeway north of Market Street, the neighborhood may become increasingly expensive for some community service providers. These existing services should be fostered and new community-serving uses should be encouraged in larger, new development. There is much the Planning Department can do, primarily through the permitting process where land use issues are reviewed, to support proposals for new facilities and resist changes that may damage existing ones. These valuable community services should be kept within a convenient walking distance. New development can significantly contribute to the neighborhood by including community serving uses in their proposals. Modern service delivery models link services to housing, and accordingly, many funding sources require on-site community service space. Proposals for a change of land use or other change would be encouraged to retain community services or facilities unless: (i) a suitable replacement service or facility is available within a convenient distance; or (ii) the use of the site/building for community service/facility purposes cannot be continued or be made viable in the longer term. POLICY 1.1.8 On the frontages indicated above, maximize neighborhood-serving retail activities on the ground floor for new development and substantial alterations, providing retail uses for at least 75 percent of the frontage on the ground floor. See Map 2 Frontages Where Retail is Required

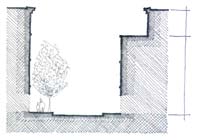

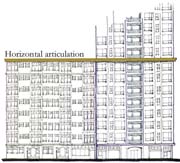

POLICY 1.1.9 In the RTO district, allow retail uses up to 1,200 square feet. Limit the hours of operation for these uses to 7 AM to 10 PM. POLICY 1.1.10 As a considerable amount of publicly zoned land will be converted from a freeway to housing, it will increase the demands on the remaining public lands in the plan area. Publicly zoned land is crucial to the functioning of a healthy city and neighborhood. Publicly zoned lands provide opportunities for crucial facilities such as schools, firehouses, libraries, recreation centers, open space, city institutions and public utilities. Over time, acquiring public land has only become more difficult and more costly. When public land that is zoned “open space” becomes surplus to one specific public use, the General Plan states that it should be reexamined to determine what other uses would best serve public needs. The Open Space Element of the General Plan states that public land both designated as “surplus” and “open space” should first be considered for open space. If not appropriate for open space, other public uses should be considered before the release of public parcels to private development. OBJECTIVE 1.2 The plan’s urban form and height proposal is based on enhancing the existing variety of scale and character throughout the plan area. The plan adjusts heights in various locations to achieve urban design goals and to maximize efficient building forms for housing, given building code, fire, and other safety requirements. The heights ensure that new development contributes positively to the urban form of the neighborhood and allows flexibility in the overall design and architecture of individual buildings. The height map on the following page implements the following policies: POLICY 1.2.1 It is the height and mass of individual buildings that define the public space of streets. Building heights have historically been strongly related to the width of streets in the Market and Octavia neighborhood and elsewhere in the city. Where building heights are related to the width of the facing streets, they enclose the street and define it as a comfortable, human-scaled space with ample light and air. The permitted heights should strengthen the relationship between the height of buildings and the width of streets, as shown in Map 3 Height Districts POLICY 1.2.2 Proposed heights in neighborhood commercial districts are adjusted to maximize housing potential within specific construction types. Where ground floor commercial is most desirable, existing 40- and 50-foot height districts are adjusted to permit an additional five feet of height provided that it is used to create more generous ceiling heights on the ground floor. It is also common in the Market and Octavia neighborhood, as with the rest of San Francisco, to provide housing above ground floor commercial spaces along neighborhood commercial streets. This not only provides much-needed housing close to services and, in most cases, transit, but also provides a residential presence to these streets, increasing their vitality and the sense of safety for all users POLICY 1.2.3

POLICY 1.2.4 Streets work well as public spaces when they are clearly defined by buildings of a similar height on both sides of the street. POLICY 1.2.5 The City’s height controls reinforce clusters of taller buildings on tops of some hills, in the downtown core, and along Market Street in the downtown. Heights increase at the Van Ness Avenue and Market Street intersection and taper down to surrounding low-rise areas. POLICY 1.2.6 The block of Market Street from Buchanan Street to Church Street marks the entrance to the Castro. At Buchanan Street, heights and form respond to Mint Hill and preserve views to the Mint from Dolores Street. At Church Street, building forms should accent this point, with architectural treatments that express the significance of the intersection. The height map allows for buildings up to 85-feet in height at the intersection of Church and Market Streets. Special architectural features should be used at the corners of new buildings to express the visual importance of this intersection. POLICY 1.2.7 Market Street is a uniquely monumental street, with buildings along its length that have a distinctive scale and stature, especially east of its intersection with Van Ness Avenue. West of Van Ness Avenue, new buildings should have a height and scale that strengthens the street’s role as a monumental public space. A podium height limit of 120-feet along Market Street is established east of Van Ness Avenue, consistent with its width. Buildings heights step down to 85 – 65-feet along Market Street west of Van Ness Avenue, providing a transition to surrounding areas. POLICY 1.2.8 Where residential towers are permitted above the width of the street (“street wall height”), establish zoning controls to ensure that tower forms allow adequate light and air to reach dwelling units and minimize shadow to streets and open spaces. To avoid a bulky appearance on the skyline, a tower’s floor plate will be regulated; floor plate size will be limited in proportion to tower height. POLICY 1.2.9 A close-knit pattern of individual buildings on small lots is what has made the Market and Octavia neighborhood successful as an urban place over time and is one of its chief assets. The neighborhood is built on a traditional fabric of lots that are small, narrow and deep, which provides for an enriching block face, diversity of buildings, and stimulating pedestrian experience. The small scale of development should be retained. POLICY 1.2.10 Residential districts in the plan area have a well-established pattern of interior-block open spaces that contribute to the livability of the neighborhood. Along some of the area’s primary streets, 65-feet and higher height districts directly abut smaller scale residential districts of 40-feet or lower height districts. Care must be taken to sculpt new development so that light and air are preserved to midblock spaces. Upper Market NCT lots that abut residential midblock open spaces will be required to provide rear-yards at all levels. Housing is an essential human need. No single issue is of more importance than how we provide shelter for ourselves. Housing is in chronically short supply in San Francisco, particularly for those with low and moderate incomes. The Market and Octavia neighborhood presents a unique opportunity, because new housing can build upon and even enhance its vitality and sense of place. This plan encourages housing as a beneficial form of infill development—new buildings at traditional scales and densities, reflecting the fine-grained fabric of the place. In many respects, this plan does not diverge from established and continually evolving citywide policies and programs of housing affordability. It does not establish new inclusionary standards, new funding mechanisms, nor create its own solutions to homelessness in the city. On these matters, which cannot be affected on an area-by-area basis, The Plan defers to larger citywide solutions. Existing sound housing stock is a precious resource and should be preserved and supported. No demolitions, removals, nor wholesale clearings as in redevelopment projects of old are proposed. Dwelling unit mergers are strongly discouraged. The fundamental principles are:

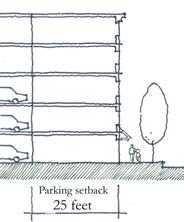

The traditional housing stock in the Market and Octavia neighborhood supports a variety of living arrangements—individual homes, flats, apartments—some owned but mostly rented, including various forms of group housing and assisted living. While the living spaces in older buildings typically have a strong relationship to the street, expressed through stoops and bay windows, newer housing often has a weaker relationship to the street, largely because of the space consumed by blank walls and garage doors that parking presents to the neighborhood. Creating housing for a diverse population includes housing people who are elderly or who have disabilities. Such people are confronted with multiple challenges in daily living. All housing types, including new affordable housing, new infill housing, and enhancements to existing housing should be mindful of these challenges and ease the burden where possible. It remains pivotal that the housing stock be as diverse as the city’s population. OBJECTIVE 2.1 The removal of the Central Freeway and construction of Octavia Boulevard has created 22 publicly owned parcels, on about 7 acres of land. In keeping with the city’s existing policy of using surplus publicly owned land to house San Francisco residents, approximately one-half of these parcels have been earmarked for affordable housing, including a substantial amount of senior housing. In keeping with the mixed-use character of the neighborhood, commercial uses are encouraged on the ground floor of new development on the freeway parcels; commercial uses are required on parcels fronting Hayes Street and portions of Octavia Boulevard. POLICY 2.1.1 The increase in property values due to the public investments in Octavia Boulevard should be coupled with the development of affordable housing on the remaining freeway parcels so that the Market & Octavia area remains a socially sustainable, mixed-income neighborhood. Affordable housing should ideally be distributed among a variety of different housing types and levels of affordability, rather than concentrated in individual projects. OBJECTIVE 2.2 There are numerous opportunities for small-scale infill housing to be constructed throughout the plan area. Every effort should be made to make it attractive and viable to build housing. New units can be added to existing residential uses, and new housing can be built on small lots—providing essential housing within the area’s established urban fabric. The plan encourages more housing to be built close to transit and services, provided that it meets the urban design and transportation objectives outlined elsewhere in this plan. POLICY 2.2.1 While appropriate in less developed areas, density maximums unnecessarily constrain the housing potential of infill development in relatively dense, established urban neighborhoods like the Market and Octavia area. Carefully-prescribed controls for building height, bulk, light and air, open space, and overall design can successfully control a building’s physical characteristics while allowing the maximum amount of housing opportunity within it. Flexibility and creativity leads to new potential consistent with the traditional fine-grained character of the area. POLICY 2.2.2 Greater unit density does not necessarily correlate to housing for more people. For new construction, the new policies are meant to allow flexibility to accommodate a variety of housing and household types, such as student, extended family, or artist housing, as well as development on small and irregular lots. For instance, the Octavia Boulevard parcels are narrow and irregular, and economically and architecturally reasonable projects will likely require more units and flexibility than earlier zoning would allow. Therefore, these controls balance the need for a flexible process that allows innovative and dense designs on irregular parcels, while also providing sufficient control so that existing housing stock and family-sized units are preserved. One goal of The Plan is to ensure the market does not produce only projects with small units. A unit mix requirement will apply to any project larger than 4 units. Subdivisions will be permitted only when the resulting units retain some larger units. POLICY 2.2.3 Minimum parking requirements are one of the most significant barriers to the creation of new housing, especially affordable housing, and transit-oriented development in the plan area. Providing parking as currently required reduces the total number of units that can be accommodated on a given site and increases the cost of individual units to residents. The amount of off-street automobile parking provided can be tailored to achieve larger community goals such as mobility, convenience, and economic development. To meet the larger goals of this plan, the parking policies for the Market and Octavia area have been developed to support the plan’s highest priorities for good place making:

POLICY 2.2.4 Several stories of housing above ground-floor commercial uses is typical on neighborhood commercial streets throughout San Francisco. This pattern links housing directly to the services on the street, provides a variety of housing types (typically more studio and one-bedroom units) and encourages a 24-hour presence of people living, shopping, and working on the street. POLICY 2.2.5 New housing can be provided incrementally without significant changes to the physical form of the area by adding accessory units to existing buildings. Because these units are typically smaller and directly attached to existing units, they are an ideal way to provide housing for seniors, students, and people with low-income or special needs. Additions to existing buildings and conversions of ground floor spaces that create new housing units are allowed and encouraged. Encourage the addition of units to existing residential buildings throughout the area. Encourage the conversion of garage spaces to housing units and the restoration of on-street parking spaces. Where such a conversion would remove off-street parking, require the removal of the curb cut and the planting of at least one new street tree. POLICY 2.2.6 Planning code policies and project review procedures can sometimes create uncertainty and ultimately raise the costs of new housing. For projects that respond to the goals and meet the standards of this plan, the permitting process should be simple and easy to administer. With clear zoning controls and urban design guidelines in place, discretionary actions requiring a Planning Commission hearing will be avoided where possible. Consistency with the policy and intent of this plan should be the primary factor in deliberations. POLICY 2.2.7 Increase affordable housing or other requirements on market rate residential and commercial development projects to provide additional affordable housing, where the Market and Octavia Plan’s zoning controls have significantly increased a site’s permitted development potential, if additional requirements would not jeopardize the financial feasibility of a proposed market rate housing or commercial development. OBJECTIVE 2.3 The Market and Octavia neighborhood has approximately 10,500 housing units today, providing homes to more than 23,000 people. In contrast to new housing, existing housing tends to be more affordable. The area’s existing housing stock should be preserved as much as possible. POLICY 2.3.1 The City’s General Plan discourages residential demolitions, except where it would result in replacement housing equal to or exceeding that which is to be demolished. This policy will be applied in the Market & Octavia area in such a way that new housing would at least offset the loss of existing units, and the City’s affordable housing, and historic resources would be protected. The plan maintains a strong prejudice against the demolition of sound housing, particularly affordable housing. Even when replacement housing is provided, demolitions would be permitted only through conditional use in the event the project serves the public interest by giving consideration to each of the following: (1) affordability, (2) soundness, (3) maintenance history, (4) historic resource assessment, (5) number of units, (6) superb architectural and urban design, (7) rental housing opportunities, (8) number of family-sized units, (9) supportive housing or serves a special or underserved population, and (10) a public interest or public use that cannot be met without the proposed demolition. POLICY 2.3.2 Dwelling-unit mergers reduce the number of housing units available in an area. If widespread, over time, dwelling unit mergers can drastically reduce the available housing opportunities, especially for single- and low-income households. This plan maintains a strong prejudice against dwelling unit mergers with the goal of maintaining the neighborhood housing stock and an appropriately balanced distribution of unit sizes. OBJECTIVE 2.4 In addition to preserving and increasing the supply of housing in the area, there is much that can be done to make housing more affordable and to reduce unnecessary costs associated with producing it. By building on the area’s existing strengths as an accessible, mixed-use neighborhood, housing costs associated with car ownership can be reduced, making housing substantially more affordable. POLICY 2.4.1 In much of the housing built under current parking requirements, the cost of parking is “bundled” into the cost of owning or renting a home, requiring households to pay for parking whether or not they need it. As part of an overall effort to increase housing affordability in the area, costs for parking should be separated from the cost of housing and, if provided, offered optionally. To support this, encourage parking provided in new residential developments to be made publicly available for lease. Encourage private developers to partner with carsharing programs in locating carshare parking in new buildings. Encourage shared use of private and public parking facilities to meet residential needs, including surplus parking available in the Opera Plaza and Civic Center Garages. POLICY 2.4.2 As part of the burgeoning LEM program, these savings can enable residents to qualify for a larger mortgage for a home. Develop programs to highlight Market and Octavia as a “location-efficient” neighborhood as part of the LEM program. POLICY 2.4.3 The city should encourage the development of a community land trust in the area, and support the exploration of other innovative approaches to reducing housing costs for homeowners and renters. POLICY 2.4.4 As part of the monitoring system, the housing stock shall be monitored for changes to unit size, type of unit mix, density and general housing character. The types of housing opportunities are closely linked to the people who will be able to live in that neighborhood. Over time, the neighborhood is sure to change in some respects. Regular monitoring reports to the public can help provide opportunity for residents to become aware of change and direct changes to the benefit of the community at large. The monitoring report shall track new development, subdivisions, demolitions and condo-conversions, especially for effects to affordable housing and historic buildings.

Buildings define the public realm in addition to providing space for a myriad of private activities. They provide the setting for people to meet and interact informally and shape the neighborhood’s range of social experiences and offerings. Building height, setback, and spacing define the streets, sidewalks, plazas, and open space that comprise the community’s public realm. Buildings shape views and affect the amount of sunlight that reaches the street. The uses of buildings and their relationships to one another affect the variety, activity, and liveliness of a place. Buildings with a mix of uses, human scale, and interesting design contribute to attractive and inviting neighborhoods, and are vital to the creation of lively and friendly streets and public spaces. In the best cases, the defining qualities of buildings along the street create a kind of “urban room” where the public life of the neighborhood can thrive. OBJECTIVE 3.1 For all new buildings and major additions, ensure that fundamentals of good urban design are followed, while allowing for freedom of architectural expression. A variety of architectural styles (e.g. Victorian, Edwardian, Modern) can perform equally well. Proposed buildings should relate well to the street and to other buildings, regardless of style. In its architectural design and siting, new construction should reflect and improve on the scale, character, and pedestrian friendliness of the street and the neighborhood. Design should be consistent with the accompanying design guidelines; the guidelines do not address architectural style. The intent is to encourage buildings with a human scale that contribute to the establishment of inviting and visually interesting public places, consistent with the area’s traditional pattern of development. Policy 3.1.1 New development will take place over time. Modest structures will fill in small gaps in the urban fabric, some owners will upgrade building facades, and large underutilized land areas, such as the former Central Freeway parcels, will see dramatic revitalization in the years ahead. The following Fundamental Design Principles apply to all new development in the Market and Octavia area. They are intended to supplement existing design guidelines, Fundamental Principles in the General Plan and the Planning Department’s Residential Design Guidelines. They address the following areas: (1) Building Massing and Articulation; (2) Tower Design Elements; (3) Ground Floor Treatment, further distinguished by street typology, including (a) Neighborhood Commercial Streets, (b) Special Streets - Market Street, and (c) Alleys; and (4) Open Space.

OBJECTIVE 3.2 There are currently a number of known historically significant resources in the plan area. Locally designated landmarks are specified in Article 10 of the Planning Code. Resources are also listed in the California Register of Historical Resources, the National Register of Historic Places, and in certified historic resource surveys. Map 4 shows these known resources.

POLICY 3.2.1 Important historic properties cannot be replaced if they are destroyed. Many resources within the Market & Octavia area are of architectural merit or provide important contextual links to the history of the area. Where possible these resources should be preserved in place and not degraded in quality. POLICY 3.2.2 Whenever possible, historic resources should be conserved, rehabilitated or adaptively used. Over time, many buildings outlive the functions for which they were originally designed, and they become vacant or underused. Adaptive use proposals can result in new functions for historic buildings. Significant, character-defining architectural features and elements should be retained and incorporated into the new use, where feasible. POLICY 3.2.3 Garage doors disrupt the original architecture and diminish the quality of the sidewalk and street. Where garages have been added to historically significant buildings, seek to return the buildings to the original character. Policies throughout this plan regulate the installation of off-street parking. Those policies should be rigorously applied to historically significant buildings. POLICY 3.2.4 Designated historic districts or conservation districts have significant cultural, social, economic, or political history, as well as significant architectural attributes, and were developed during a distinct period of time. When viewed as an ensemble, these features contribute greatly to the character of a neighborhood and to the overall quality, form, and pattern of San Francisco. Historic districts can provide a cohesive vision back in time, allowing the City’s current residents to experience a larger context of the urban fabric, which has witnessed generations. The boundaries of recognized districts can be found on Map 4. POLICY 3.2.5 The following districts that have been identified within the Plan Area: Duboce Park Duboce Triangle Hayes Valley Residential Hayes Valley Commercial The “commercial” moniker given to the district is indicative of the types of contributing resources that are prevalent throughout the area. Primarily, these take the form of 1 - 3 story commercial buildings and mixed-use residential and commercial structures. A few industrial buildings are also located in the district—notably auto repair shops—but these are also considered contributing because of their quasi-commercial use. The contributing buildings are primarily of wood frame construction, with masonry and concrete construction in the minority. The earliest contributor dates to circa 1885, while the latest dates to 1927. San Francisco State Teacher’s College Vicinity Apartments San Francisco State Teacher’s College Upper Market Street The properties fronting on Market Street are almost entirely commercial. Nearly all of the buildings are of wood frame construction and clad in wood or stucco siding. Other building types include concrete construction and brick masonry. Victorian-era and Classical Revival style the most prevalent, however International, Art Deco, and Art Moderne, are also present and help to illustrate the continual commerce-driven development of parcels along the prominent traffic corridor. In keeping with commercial stylistic conventions, rectangular, flat roofed structures are prevalent. Bay windows and facades organized into multiple bays are common features throughout the district. Elgin Park-Pearl Street Reconstruction Jessie-McCoppin-Stevenson Streets Reconstruction Ramona Street Guerrero Street Fire Line Hidalgo Terrace These resources and any other potential districts identified through future survey efforts should be preserved, maintained and enhanced through rigorous review of any proposed changes within their boundaries. POLICY 3.2.6 A 1995/96 historic resources survey identified an historic district in the Hayes Valley area and the Inner Mission North Survey of 2004 identified three smaller eligible districts in the north Mission area. The Market and Octavia Historic Preservation Survey expanded one existing district and identified an additional 7 districts. The boundaries of these historic districts can be found on Map 4. Future survey findings should be incorporated as appropriate. In addition to the protection provided to these resources through planning and environmental review procedures, official designation should also be pursued when appropriate. Designation serves to more widely and publicly recognize important historic resources in the plan area. POLICY 3.2.7 Historic resources are focal points of urban context and design, and contribute greatly to San Francisco’s diverse neighborhoods and districts, scale, and city pattern. Alterations, additions to, and replacement of older buildings are processes by which a city grows and changes. Some changes can enhance the essential architectural and historical features of a building. Others, however, are not appropriate. Alterations and additions to a landmark or contributory building in an historic district should be compatible with the building’s original design qualities. Rehabilitation and adaptive use is encouraged. For designated resources, the nationally recognized Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties should be applied. For non-designated cultural resources, surveys and evaluations should be conducted to avoid inappropriate alterations or demolition. POLICY 3.2.8 New buildings adjacent to or with the potential to visually impact historic contexts or structures should be designed to complement the character and scale of their environs. The new and old can stand next to one another with pleasing effects, but only if there is a successful transition in scale, building form and proportion, detail, and materials. Other polices of this plan not specifically focused on preservation—reestablishment and respect for the historic city fabric of streets, ways of building, height and bulk controls and the like—are also vital actions to respect and enhance the area’s historic qualities. Policy 3.2.9 Preservation incentives are intended to encourage property owners to repair, restore, or rehabilitate historic resources in lieu of demolition. San Francisco offers local preservation incentive programs, and other incentives are offered through federal and state agencies. These include federal tax credits for rehabilitation of qualified historical resources, property tax abatement programs (the Mills Act), alternative building codes, and tax reductions for preservation easements. Preservation incentives can result in tangible benefits to property owners. POLICY 3.2.10 The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards assist in the long-term preservation of historic resources through the protection of historical materials and features. Nationally, they are intended to promote responsible preservation practices that help to protect against the loss of irreplaceable cultural resources. POLICY 3.2.11 These standards should be applied in decisions involving infill construction within conservation or historic districts. These districts generally represent the cultural, social, economic or political history of an area, and the physical attributes of a distinct historical period. Infill construction in historic districts should be compatible with the existing setting and built environment. POLICY 3.2.12 Valuing the historic character of neighborhoods can preserve diversity in that older building stock, regardless of its current condition, is usually of a quality, scale, and design that appeals to a variety of people. Older buildings that remain affordable can be an opportunity for low-income households to live in neighborhoods that would otherwise be too expensive. POLICY 3.2.13 Where rehabilitation requirements threaten the affordability of housing, other accommodations may need to be emphasized such as: exterior rehabilitation which emphasizes the preservation and stabilization of the streetscape of a district or community or recognizing funding constraints, to balance architectural character with the objectives of providing safe, livable, and affordable housing units.

The System of Public Streets and Alleys In San Francisco as a whole and in the Market and Octavia neighborhood, streets are the public realm. We travel along public ways, to get from place to place, and to gain access to where we live, work, and shop. Public services—police, fire, deliveries of all sorts—depend on them. We locate our municipal hardware and utilities—water, sewage and electric lines, cables, and more—on them, above them, and mostly under them. But the public way system is much more than a utilitarian system of connections. It is where people walk, where they meet each other, where they socialize, where they take in the views, where they see what merchants have to offer, where they get to know, first hand, their city, their neighborhood, and their fellow citizens. Streets, then, connect us socially and functionally, and can be categorized as safe or dangerous, places to behold or to stay away from. It is from this dual nature of streets as places of function (utility, transportation) and places of socializing and leisure that one of the main dilemmas of planning arises—how do we allocate this most scarce public resource characterized by both functional requirements and aesthetic sensibilities. The Market and Octavia neighborhood is within walking distance of Downtown, adjacent to Civic Center, the home of San Francisco’s most important main street, located where three of the oldest of the grids come together. It is reasonably level (for San Francisco), which makes it great for walking and biking. Given its central location, it is one of those urban areas that most San Franciscans are compelled to pass through in order to reach their destination. Whether by streetcar, bus, trolley, rapid transit, auto, bicycle, or on foot, many of the City’s movement systems pass through the area. They do it on the neighborhood’s system of public ways. The challenge in Market and Octavia is no different than for planning in general: How do we accommodate the legitimate travel needs of the people using the many modes of movement through the area, while at the same time respecting and achieving the neighborhood’s legitimate desires for and expectations of safe, moderate-paced, attractive streets on which to move, socialize, walk, and lead an urban, face-to-face lifestyle, at least the equal to any in San Francisco. A first step to meeting that challenge is to restore a balance between the movement needs of competing travel modes, and to ensure that there is a balanced mix of travel modes with special attention to pedestrians and street life. The plan recognizes that road capacity in San Francisco is a highly constrained resource, with decision-makers required to balance the requirements of cars, transit vehicles, freight, cyclists, and pedestrians. A common fear is that reducing the capacity available for cars will result in major increases in congestion. Much research rejects this logic and shows that people’s transportation choices are dynamic and respond to capacity, relative cost, time, convenience, and other factors. Crucially, we learn that movement of people is more than just movement of cars. This plan prioritizes the safe and effective movement of people. What follows are specific proposals for a myriad of improvements to streets. See Map 5. System of Civic Streets and Open Space

Principle: Streets that support and invite multiple uses, including safe and ample space for pedestrians, bicycles, and public transit, are a more conducive setting for the public life of an urban neighborhood than streets designed primarily to move vehicles. The past 20 years have seen advances in ways to improve the livability of streets, be they major traffic carriers or local public ways. Closely planted street trees, pedestrian-scaled lights, well marked crosswalks, widened sidewalks at corners, and creative parking arrangements are but a few of the methods used with success to achieve the kind of neighborhood that residents say they want. They are all addressed in the objectives and policies that follow. Parks, Plazas and Open Spaces Provision of public open space is necessary to sustain a vital urban neighborhood, especially one where new housing is to be added to an already dense urban fabric. This is especially so given the reality that there are few public parks or plazas in the Market and Octavia neighborhood. To be sure, there are public spaces nearby: Jefferson Square between Gough Street and Laguna Street, at Turk Street; Civic Center Plaza (with its children’s play areas) east of Polk Street; Dolores Park some blocks south of Market Street; Duboce Park, west of Steiner Street; and Koshland Park, which perhaps comes closest to what one thinks of as a local park, up on the hill, at Buchanan Street and Page Street. But all of these spaces are either “nearby,” close but not a part of, or are city-oriented rather than neighborhood-oriented. There is no central public square, park, or plaza that marks and helps give identity to this neighborhood. At the same time that the neighborhood lacks community-focused open space, it is also largely built out, without significant or appropriate undeveloped land, except for that laid bare by the demolition of the Central Freeway. Most of this property is earmarked for much-needed housing. In the Market and Octavia neighborhood, the streets afford the greatest opportunity to create new public parks and plazas. That is why streets are included in the discussion of public open spaces. This plan takes advantage of opportunities within public rights-of-way. Most noteworthy, Octavia Boulevard itself is conceived in part as a linear open space, as with all great boulevards, that will draw walkers, sitters, and cyclists. In addition, modest but gracious public open spaces are designated within former street rights-of-way that are availed through major infrastructure changes, along with a series of smaller open spaces, for the most part occurring within widened sidewalks areas. As well, housing development along the former freeway lands will create open spaces within private developments, contributing to the neighborhood as a whole. Principle: A successful open space system is carefully woven into the overall fabric of a neighborhood’s public streets, taking advantage of opportunities, large and small, to create spaces both formal and informal. While almost all of the Market and Octavia neighborhood is built out, there are a few opportunities to integrate new neighborhood open spaces into its existing physical fabric. There are several significant sites for potential new open spaces. Widened sidewalk areas, when provided with benches that encourage lingering and trees that provide shade, can be effective small public spaces. This plan includes proposals for both kinds of open space.

Areawide Improvements Local streets like Laguna, Hermann, Octavia north of Hayes, Buchanan, and others should be reconfigured and enhanced where necessary to encourage walking and slow traffic movement. They are envisioned as gathering places that enhance neighborhood identity as well as public streets. The neighborhood’s alleys are major assets to be protected and, in places, enhanced. OBJECTIVE 4.1 POLICY 4.1.1 On streets throughout the plan area, there is a limited amount of space on the street to serve a variety of competing users. Many streets have more vehicular capacity than is needed to carry peak vehicle loads. In accordance with the city’s Transit-First Policy, street rights-of-way should be allocated to make safe and attractive places for people and to prioritize reliable and effective transit service—even if it means reducing the street’s car-carrying capacity. Where there is excessive vehicular capacity, traffic lanes should be reclaimed as civic space for widened sidewalks, plazas, and the like. Though it may not be possible to widen sidewalks along major traffic streets such as Market, Franklin, Gough, Oak, and Fell Streets, it is both possible and desirable to widen sidewalks by providing widened ‘sidewalk bulbs’ at corners. In addition, boldly marked crosswalks alert drivers that they are entering intersections where pedestrians are likely to be crossing. Sidewalk widening and improved pedestrian crossings should be implemented throughout the plan area as the most important means of improving pedestrian safety and comfort on the street. See Map 6. Priority Intersections for Pedestrian Improvements POLICY 4.1.2 Closely spaced and sizeable trees parallel and close to curbs, progressing along the streets to intersections, create a visual and psychological barrier between sidewalks and vehicular traffic, like a tall but transparent picket fence. More than any other single element, healthy street trees can do more to humanize a street, even a major traffic street. On many streets within the Market and Octavia neighborhood, successful environments can be created through consistent tree infill. For example, this can take place on Otis, Mission, Franklin, and Gough Streets north of Market Street. On other streets, such as Gough Street south of Market, Fell, and Oak Streets, and Duboce Avenue, it will require a major new tree planting program. Consistent tree plantings make an important contribution to neighborhood identity. Different tree species can be used on different streets, or even different blocks of the same street, thereby achieving diversity on a broader basis. Rather than removing existing trees from any given street, the dominant tree species—or preferred tree species—on each block should be identified and future tree planting should be of that tree type. See Map 7 Priorities for Street Tree Plantings

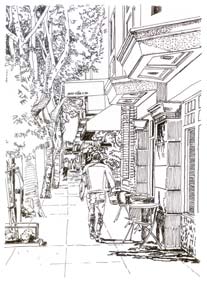

POLICY 4.1.3 Transit-oriented neighborhoods and pedestrian-friendly environments depend on good pedestrian access and ease of movement. Some intersections in the plan area do not permit pedestrian crossings, for example Fell and Gough, Hayes and Gough, and Gough and Otis. The signal cycles at these intersections should be adjusted to accommodate pedestrians . The City should also eliminate pedestrian “do not cross” signs as the sole means to resolve problems at high-traffic intersections where it may be done safely. Prohibitions on pedestrian crossings should be removed wherever these bans exist throughout the plan area. POLICY 4.1.4 Public art plays an essential role in the civic life of our city. In urban places like the Market and Octavia neighborhood, where streets, parks, and plazas are where civic life unfolds, public art takes on a broad range of meanings that enriches the overall quality of public space. Funding and space for public art should be integrated into all proposals for the physical improvement of streets and open spaces. POLICY 4.1.5 There are many existing alleys within the plan area, many of which are concentrated in Hayes Valley and in the larger blocks in the South of Market areas. In addition to being the location of considerable neighborhood housing, most of the alleys, by reason of their intimate scale, the diversity of buildings along them, in some cases their trees, and certainly their contrast with surrounding streets, are delightful, valuable urbane places. These alleys are an invaluable part of the neighborhood’s system of public ways and, like any public resource, should be protected against proposals to privatize them. POLICY 4.1.6 A number of alleys which were previously through streets have been truncated and are now dead-end alleys. As part of the effort to extend pedestrian connections, the City should purchase of the easternmost portion of Plum Alley that is in private ownership and further study the extension of Stevenson Alley from Gough Street to McCoppin Street as part of any proposal for demolition and new construction on Assessor’s Block 3504/030. POLICY 4.1.7 Parking should be concentrated along the curbside with the fewest curb cuts (driveway breaks). New pedestrian-scaled lighting can be added. Street trees should be planted (if residents desire trees). Seek to reach agreement on a single tree species by street (or at minimum, per block) in order to have a unified planting pattern. Because alleys carry relatively little traffic, they can be designed to provide more public space for local residents—as a living alley with corner plazas to calm traffic, seating and play areas for children, with space for community gardens and the like— where people and cars share space. By calming traffic and creating more space for public use, the alley can become a common front yard for public use and enjoyment. Working closely all City agencies should develop design prototypes for more extensive improvements to residential alleys. The City should establish a process for local residents to propose living-street improvements and participate actively in the design for their alley.

See Map 8. Alleys for “Living Alley” Improvements, Figure 5. A Living Alley, and Figure 6 Linden Alley: Before and After

POLICY 4.1.8 Certain alleys support non-residential uses. Coordinated approaches to the design of these alleys should protect the intimate scale of these alleys and yet create public space that contributes to and supports the varied uses along them.

Octavia Boulevard and Hayes Valley OBJECTIVE 4.2 POLICY 4.2.1 Bringing the elevated freeway down to street surface at Market Street provides the opportunity to create two new small public open spaces: a plaza along Market Street west of the freeway touchdown, and a plaza or other form of small open space within the last block of McCoppin Street, as it comes to its terminus west of Valencia Street. The plaza on Market Street enhances the pedestrian experience of the street, and facilitates safer pedestrian crossings. Because of its prominent location at the end of the freeway and beginning of Octavia Boulevard, it has been designed to signal the end of the freeway and an entry to the city. The plaza should include seating, trees and other pedestrian amenities. The leftover space on McCoppin Street is an appropriate place to provide a community-serving open space, integrated into the overall “green street” treatments proposed for McCoppin Street east of Valencia Street, as well as the proposed bike path on the east side of the touchdown. The triangular parcel immediately south of the McCoppin Street right-of-way could be incorporated with it to provide a larger open space at this location.

POLICY 4.2.2 Hayes Street is a special commercial street within the neighborhood. It is at once locally-focused, with small cafes and restaurants, and oriented citywide, with numerous galleries and close proximity to cultural institutions in the Civic Center. It is often alive with pedestrian activity. Between Franklin and Laguna Streets, where traffic rerouting policies allow converting the street back to two-way traffic, the roadway is wider than it needs to be for vehicular traffic. In this area, the City should undertake a future study which would consider factors such as widening the sidewalk on the north side of the street, planting new trees, and installing new pedestrian-scaled light fixtures and benches to create a much needed public open space. Café seating should be allowed to spill out onto widened sidewalks. The sidewalk widening should not adversely affect turning movements for Muni buses. See Figure 7. Hayes at Gough Intersections: Existing and Proposed

POLICY 4.2.3 Damage done to the San Francisco grid by land-assembly projects of the 1960’s and 1970’s can be partially repaired through the reestablishment of Octavia Street as a public right-of-way from Fulton Street to Golden Gate Avenue, providing improved pedestrian access to existing housing developments, helping to knit them back into the areas south of Fulton Street, and providing a “green connection” between the new Octavia Boulevard, Jefferson Park and Hayward Playground. Bicycle movement in a north-south direction would also be improved by this policy. POLICY 4.2.4 In the long-term, the City should evaluate removing the Central Freeway west of Bryant Street, and to rebuilding Division Street as an extension of Octavia Boulevard. The success of Octavia Boulevard should be analyzed periodically in conjunction with a study of further dismantling of the Central Freeway. Just as the north-of-Market Street Central Freeway ramps bisected the Market and Octavia neighborhood, the new Central Freeway ramp does the same thing to the south. The area under the freeway is dark and dank and Division Street and its surrounds are unpleasant at best. While pulling the Central Freeway back to Market Street allows the repair of Hayes Valley with minimal negative impacts to cross-town automobile traffic, it does nothing to address the damage done to the Mission District or SoMa West. As important, it disgorges a large volume of high-speed automobile traffic onto Market Street, the most constrained street in the plan area. Market Street is the city’s signature street, its most important civic street and the most important for transit, bicycles, and pedestrians. The considerable damage the freeway touchdown has done to the city’s most important street is obvious, and the City should purposefully work to repair this damage. South of Market Street, the Mission Street and South Van Ness Avenue freeway ramps are poorly placed, requiring motorists to make left turns through highly congested intersections to get to and from the Van Ness/Franklin/Gough corridor. These turning movements add delay in already constrained locations, particularly at the Mission/Otis/Duboce/13th intersection. To take better advantage of the SoMa and Mission street grids – and particularly the extra capacity on Brannan, 11th, 12th and northeast Mission Streets, the City should study removing the elevated Central Freeway to the fullest extent feasible, and rebuilding Division Street as a surface-level extension of Octavia Boulevard. Market Street Market Street, the City’s “Grand Diagonal,” will continue to be honored and protected as San Francisco’s visual and functional spine. Market Street has been reconfigured twice in major ways since a 1967 bond issue was approved by San Franciscans to improve it from the Central Freeway to the Ferry Building. This plan confines itself to a series of enhancements to make the street more pleasant to walk along, cross, and cycle upon in the plan area. Improvements to the overall street configuration should be made as part of a comprehensive redesign of the street, from The Embarcadero to Castro Street. Ultimately, the damage done to Market Street and the neighborhood by the poorly conceived freeway touchdown should be addressed and repaired. OBJECTIVE 4.3 POLICY 4.3.1 Market Street is unquestionably the City’s most memorable street. It is our primary ceremonial space, the heart of our downtown, and our most important transportation corridor. There are more demands placed on Market Street than any other street in the City: it accommodates streetcars, buses, trolleys, automobiles and pedestrians who use it as a major route to destinations and as a strolling street. POLICY 4.3.2 While an appropriate redesign of the whole of Market Street is outside of the scope of this plan, significant improvements of moderate cost are possible and desirable to enhance the street within the neighborhood. The magnificent palm trees that march down the center of the street are spotty and noncontiguous in their spacing, and their impact is lost where they are experienced: on the street. There are many opportunities to infill these trees with new ones. Similarly, there are many opportunities for additional trees along the street, at times in double rows. Both existing and new trees should receive the highest level of on-going care. Sidewalks along the street are cluttered with a disarray of newspaper boxes, signs, refuse cans, and utility boxes, which could be clustered more attractively. Benches and pedestrian-scaled lighting fixtures should be provided on the street, particularly at corner plazas. POLICY 4.3.3 The designs for these principal intersections should include streetscape elements—such as special light fixtures, gateways, and public art pieces—that emphasize and celebrate the special significance of each intersection. Market Street and Van Ness Avenue Market Street and Octavia Boulevard Market and Dolores Streets See Figure 8. Market Street at Dolores Street: Existing and Proposed

POLICY 4.3.4 Church Street, from Market Street to Duboce Avenue, is one of the city’s most important transit centers. It is also a center of neighborhood activity, with large volumes of pedestrian and bicycle traffic around the clock. Despite its prominence, the area lacks all but the most basic pedestrian amenities. Relatively simple improvements would dramatically enhance pedestrian and transit rider comfort in the area, making transit a more attractive travel option. The City should conduct a redesign study of Church Street, north of Market Street. The study should examine re-designing the street as a pedestrian-oriented transit boulevard (e.g., a transit conflict street) or other options that maximize pedestrian and transit connections. The city should also investigate the opportunity to install an enhanced streetcar-loading platform on Duboce Avenue, west of Church Street. The study should strive to ensure safe, convenient and comfortable pedestrian connections to transit facilities and to accommodate bicycle traffic on Duboce Avenue. Church Street, south of Market Street, features wide sidewalks. Special light fixtures should be installed at this intersection, and the streetcar platform shelters could receive a special “Market Street” design. See Figure 9. Market Street at Church Street: Existing and Proposed

Policy 4.3.5 East of Church Street, beyond the Muni Portal and beneath the Mint, Duboce Avenue is presently not much more than a utility yard (albeit one where colorful old streetcars are kept) and the site of an important, well-used bike path passing through. This site can be transformed into a museum that celebrates San Francisco’s streetcar history. An overhead shed-like structure would provide space for a working museum, while at the same time retaining a public path along its southern edge for bicycles and walkers. The new structure would provide a much friendlier edge to this public right-of-way than currently exists. See Figure 10. Page Street at Buchanan Street: Existing and Proposed

POLICY 4.3.6 The very wide BART and Muni entrances and the sidewalks behind them are presently somewhat moribund and hard to recognize. The city should investigate opportunities to create more visible BART/Muni entranceways on Market Street with modest vertical elements to better announce the entries. These areas should also provide small open spaces with sitting areas, integrated news-vending boxes, pedestrian lighting, and information and sales kiosks.

Historically, the Market and Octavia neighborhood has been an imminently walkable place with good access to public transit. Its dense fabric of streets and alleys, relatively gentle topography, and role as the gateway to downtown from neighborhoods to the west have made it an essential crossroads, supporting the development of strong residential districts interspersed by active commercial streets with good transit service. Since the 1950’s, these qualities have become increasingly fragile. With the proliferation of private cars in San Francisco and the region, the Market and Octavia neighborhood’s role as a crossroads has led to the imposition of a major regional freeway and the channeling of large flows of auto traffic on Fell, Oak, Gough and Franklin Streets. Because space in the area’s dense physical fabric is limited, increasing auto ownership has meant more space dedicated to the movement and storage of automobiles. This has resulted in less space for housing and more space devoted to parking—resulting in dead ground-floor spaces, overly-trafficked streets, and less room for safe sidewalks, bicycles and transit. Minimum parking requirements for new development, adapted from suburban jurisdictions and introduced in San Francisco in 1957, resulted in more space used for parking in the neighborhood, where driving has the most negative impact, and other ways of getting around are attractive and viable. Today, the Market and Octavia neighborhood is at a critical juncture. Over the last 40 years, this imbalance has created increased conflicts between cars and people, undermining the ability to provide housing and services efficiently, degrading the value of streets as the setting for public life, and crippling the potential of transit, bicycling, and walking to provide safe and convenient means of getting around. Ultimately, we can provide adequate, affordable housing and vital, healthy neighborhoods only as we restore a balance between the transportation choices available to people. How we allocate space on city streets and how much parking we provide become basic matters of geometry, not ideology: where travel demand is greatest, the allocation of street space must prioritize transit and other modes that move people more efficiently, even if it means reducing space for private autos. While autos will continue to have a place, keeping our streets running means giving priority to ways of getting around that make more efficient use of increasingly limited street space, and limiting the traffic-generating effects of parking where it is most harmful. At base, what this means is going back to a model of city building that strengthens neighborhoods like Market and Octavia, in keeping with its best traditions as an urban place. To this end, this plan proposes policies to strengthen the area’s accessibility by foot, bicycle, and transit, and to prioritize these modes as the long-term vision for how the area will grow. The plan discourages new parking facilities, recognizing that they generate traffic, consume space that could be devoted to housing, and have a negative effect overall on the neighborhood. Principle: Prioritize the efficient movement of people and goods and minimize the negative effects of cars on neighborhood streets. Responding to the “Transit-First” Policy means fundamentally changing the way we classify and plan for streets. This plan aims to make this change in the Market and Octavia neighborhood. In keeping with the “Transit-First” Policy, this plan aims to improve the reliability, frequency, and overall dignity of transit, bicycle, and pedestrian service and amenities in the area while managing the parking supply to provide efficient and equitable access to a variety of users. Principle: Better management of existing resources is more effective in improving service than simply increasing capacity. The easiest way to improve transit speed and reliability, for example, is to move existing transit vehicles faster by getting them out of traffic. A perceived lack of customer parking can be remedied by metering on-street spaces for short-term use. Management can effectively influence people’s choice of travel mode, as the region has demonstrated with tolls on the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges that support regional transit service. Management can also be used to balance parking supply and demand, as the city has shown with short-term pricing at the 5th and Mission Garage and other city garages, which discourage all-day commuter parking and encourage short-term customer parking. Making Public Transit Work Transit riders, like all travelers, are rational decision makers. They are transportation consumers, and they are looking at what is the best value for their needs. Any given traveler will not select a travel mode if it is more time consuming, less convenient, less reliable, and equally costly. The primary factors that influence mode choice are:

To this end, the plan prioritizes the frequent and reliable operation of transit on the city’s core transit streets. The plan also calls for improving the function and design of essential transit facilities and nodes. As more people come to the neighborhood, we have to give them good reasons to come without a car. OBJECTIVE 5.1 For transit to meet the needs of San Francisco’s population, it must offer travel times and reliability that compete well against the private automobile. Unfortunately, congestion has a disproportionate impact on transit relative to cars, given transit’s fixed routes and passenger boarding needs. Moreover, traffic-light systems that are timed to benefit autos often force transit vehicles to “bunch” together, decreasing reliability for passengers. These problems can be overcome by providing transit-preferential treatments, from traffic signal prioritization to creating dedicated transit rights of way, where buses and streetcars are removed from the traffic around them. If the goal of the transportation system is to maximize the movement of people, street improvements that give transit a clear priority over private vehicles are essential. In some cases this may require reallocating street space from automobiles to transit. See Map 9. Proposed Transit Improvements

POLICY 5.1.1 Market Street At the confluence of San Francisco’s three main grids, a significant share of all Muni lines converge on Market Street. At Market Street at Van Ness Avenue, five lines come together and run on average every two minutes in each direction, not counting subway service. Closer to downtown, thirteen Muni lines are scheduled every 40 seconds in each direction. With so many lines in one place, seemingly insignificant delays can quickly compound through the system. For example, a continuous one-minute delay for all Muni vehicles on Market Street at O’Farrell Street results in a cumulative 2,300-minute daily delay, significantly reducing reliability system-wide. That is equal to 38 hours of service. Over the course of a year, the extra cost to the city would exceed $1 million. Market Street’s importance to the success of the whole transportation system cannot be overstated. In addition to urban design improvements to make Market Street more friendly to pedestrians, it is critically important that the operations of Market Street be improved to eliminate Muni delays. Two important ways of achieving this are by refining signal timing and creating enforceable transit-only lanes. In order for signal timing to work without creating unnecessary red time for the cross streets, it is critical that other vehicles not impede Muni’s progress. Currently, so many cars use Market Street in the downtown that it may take several light cycles for the buses and streetcars to move to the next block - delays occasionally in excess of 10 minutes. The existing “bus only” lanes are not clearly marked, are generally not enforced, and are thus ignored by motorists. The City should consider the following means to improve transit speed and reliability:

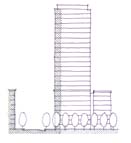

Van Ness Avenue Along with Market, Mission, Geary and Stockton Streets, Van Ness Avenue is one of the most critical links in the City and regional transit system. Besides the core Muni lines that run the length of it, it is also served by seven Golden Gate Transit lines, connecting San Francisco to points throughout Marin and Sonoma counties. It is also U.S. 101, a state highway and major auto route. As a result, it experiences severe peak period congestion, which in turn creates equally severe reliability problems and travel time impacts for the transit routes that serve it. Van Ness should be thought of as part of the core Muni Metro system. While it is not a candidate for light rail at this time because of its lack of connectivity to the rest of the system, the high number of buses in this transit corridor suggest that it would be better developed with “bus rapid transit” (BRT): an at-grade, rubber-tire version of a subway line. Such systems have been highly successful all over the world. In North America, Ottawa has a network of high-quality buses that operate as subways, Los Angeles has implemented Phase 1 of such a program on the Wilshire/Whittier corridor, and AC Transit has recently decided to implement such a system on the Telegraph/Broadway/International Boulevard corridor in Berkeley and Oakland. San Francisco is now in the process of investigating the feasibility of bus rapid transit on Van Ness Avenue. The illustration at right shows a possible solution, however the specifics of the project are yet to be determined and would require further study. See Figure 11. South Van Ness Avenue from Market to Howard Streets